SABBATH HISTORY I

BEFORE

THE BEGINNING OF MODERN DENOMINATIONS

BY

AHVA JOHN CLARENCE BOND, M.A., D. D.

AUTHOR OF "RECONSTRUCTION MESSAGES" "THE CHALLENGE OF THE

MINISTRY"

"THE SABBATH" ETC.

AMERICAN SABBATH TRACT SOCIETY

PLAINFIELD. N. J.

Copyright 1922

American Sabbath Tract Society

Second Edition

1927

TO

MY WIFE

WHOSE SYMPATHETIC CO-OPERATION AND

LOVING SACRIFICE

MADE POSSIBLE SPECIAL STUDY AND RESEARCH THIS LITTLE VOLUME

THE FIRST MATERIAL FRUITS OF THAT STUDY IS DEDICATED

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

A Growing Regard for Bible Authority

CHAPTER TWO

The Sabbath in the Old Testament

CHAPTER THREE

The Sabbath in the Gospels

CHAPTER FOUR

The Sabbath in the Early Church

CHAPTER FIVE

The No-Sabbath Theory of the Early Reformers

CHAPTER SIX

The Sabbath in the Early English Reformation

CHAPTER SEVEN

John Trask and the First Sabbatarian Church in England

CHAPTER EIGHT

Theophilus Brabourne an Able Exponent of Sabbath Truth

CHAPTER NINE

A Sabbath Creed of the Seventeenth Century

OLD SEVENTH DAY BAPTIST MEETING HOUSE AT WESTERLY, RHODE

ISLAND. Built about the year 1680, by the church then known as the Westerly

Church, now known as the First Hopkinton Church.

OLD SEVENTH DAY BAPTIST MEETING HOUSE AT WESTERLY, RHODE

ISLAND. Built about the year 1680, by the church then known as the Westerly

Church, now known as the First Hopkinton Church.

CHAPTER ONE

A Growing Regard for Bible Authority

DURING the last several years the Christian

church has been passing through a period of renewed and unusual testing. This

may be said to be a twofold experience of the church. For a period of

twenty-five years and more the church has been undergoing a process of

intellectual readjustment. This revision of its thinking was made necessary

because of the new world into which the church had been thrust by the

well-defined principles and revelations of modern science, and by the historical

method in education, which the theologian could not escape. This readjustment

was largely doctrinal. Its motives and methods had their origin within the

church, working from within outward, and resulted in the revision of certain conceptions

of truth. Men began to discriminate in their thinking between the

fundamental truths of Christianity and the mere traditions of an unholy past,

the clinging deposit of the Dark Ages. It is true that the motives of the

scholars were not always holy, nor their methods the most wholesome.

Consequently their conclusions were not always reliable. There was often,

lacking the warmth and glow of a living faith in the Christ of the Gospels.

This process was in the main constructive however, and a deal of Christian

truth was rediscovered, as the rubbish of a paganized church, the accumulation

of years of weakness and compromise, was removed by this critical and

scientific study.

The second period in the development of the

life of the modern Christian community is more constructive. It consists

in the practical adjustment of doctrine to life, and the application of the

life of faith to the problems of a distraught world.

The church is still in this new constructive

period, which doubtless it has but fairly entered. Doctrinally the church goes

forward by going back. No longer is it possible to sit supinely down and

carelessly toss to one side a cherished tradition with nothing vital to take

its place. Driven as the church has been to seek a more solid foundation for

its faith, the Bible is taking a new and vital place in the lives of men and

has become the basis of Christian doctrine, and of ethics as well. The

testimony of history to the value of doctrine may not be ignored, but it must

be in harmony with the Bible. Certain truths of Scripture, long covered up by

tradition, are coming in for a new evaluation. Certain fundamental truths of

the ages are being brought to the fore and filled with new significance and

power.

It has come to be a conviction of many hearts

that the present and compelling need of every man, and of all men everywhere,

is a new sense of the presence of God in the world. To uncover in the heart of

man his native longing for God, and to make him keenly conscious of the divine

immanence, is the supreme task of the church of Jesus Christ. It is the

business of the church to discover the means of divine grace that has been

provided for man, and to administer such in the fear of the Lord and for the

cure of souls. The source of this divine revelation is the Bible. From it men

draw their inspiration, and by the light of its teachings their feet are

guided. In the work of rescuing men from the thraldom of sin and leading them

out into the saving light of truth, the church finds in the Word of God both

its pole-star and its power.

Seventh Day Baptists, in common with other

evangelical denominations, accept the Bible as the rule of faith and practice.

They are not particularly interested in establishing an unbroken

"apostolic succession," either for ministerial orders or for church

ordinances. They are content to know that a proposed doctrine or duty is

enjoined in the Word of God and has the sanction of the Master. If this be

true, it matters not what has been the attitude of the church historic; it

becomes a part of the teaching and practice of the church present and future.

They believe in the priesthood of all believers, and are familiar with the fact

that the ecclesiastics are not always right. While not ignoring tradition as an

asset to faith, they minimize the value of tradition mediated through a special

and perpetual priesthood, and magnify the Word of God mediated by the Holy

Spirit acting directly upon the souls of men. History, however, in the

large-vindicates truth, and emancipates human life. It brings to men of the

present generation the results of the experience of the race in the laboratory

of time. It corrects many of the false conclusions of science which deals with

secondary causes only, and which has no right, therefore, to arrogate to itself

final authority in interpreting human experience.

The Sabbath can not escape the pragmatic

test now being applied to every doctrine and practice of the church. If the

Sabbath could escape, that very fact would go far toward proving its lack of vital

worth. In the face of a distraught world, crying out for the saving Gospel of

Jesus Christ, and in the face of a feverish advocacy of Sunday laws to arrest

the rising tide of worldliness, Seventh Day Baptists bring to the church,

humbly but confidently, the Sabbath of Christ as their peculiar contribution.

This they do I while, joining with all followers of the common Lord of all

Christians in every possible service which can be better promoted by such

cooperation. It is the hope of the author that through these chapters the

position of modern Sabbath-keeping evangelical Christians may be better

understood.

CHAPTER TWO

The Sabbath in the Old Testament

ONE of the institutions provided for the

blessing of man as set forth in the Sacred Scriptures is the Sabbath. The place

of the Sabbath in making known to man the love and care of God, and its place

in promoting the worship of God, are matters which the conscientious student of

the Word may not escape.

No institution of the Hebrew religion had

greater disciplinary influence upon the chosen people of God, or more fruitful

life-giving results, than the Sabbath. The Jews believed in a transcendent God

who created the heavens and the earth, and who dwells outside of and beyond the

earth, and who is greater than all that he created. They believed also in an immanent

God who lives with men; who walked in the garden with our first parents,

who talked with the patriarchs, and who inspired the prophets. His loving,

active interest in man was revealed in the fact that he created not only a

physical world, inhabitable by man, but in the morning of the

world, "when the stars slid singing down their shining way," God

created the Sabbath for rest and spiritual communion.

According to the creation story as recorded

in the first verses of Genesis,(1)the earth was not made

fit for the abode of man when all creature comforts had been provided, but only

when the continued presence of God had been assured through the symbolism of a

holy day. There is a great truth in this creation narrative, back of which man

cannot go. In the beginning God; and God created the heavens and the earth - and

the Sabbath. The crowning work of creation was the creation of the

Sabbath. This seems to be the theme of the first creation story. Scholars

affirm it as their belief that it was written not primarily to describe the

creation of the physical world, but to set forth the divine origin of the

Sabbath. This conclusion is in accord with the fact that the Bible is a book of

religion and not of science.

In commenting upon this passage in Genesis

Prof. Skinner says:

"The section contains but one idea,

expressed with unusual solemnity and copiousness of language-the institution of

the Sabbath. It supplies an answer to the question, Why is no work done on the

last day of the week? The answer lies in the fact that God Himself rested on

that day from the work of creation, and bestowed on it a special blessing and

sanctity. The writer's idea of the Sabbath and its sanctity is almost too

realistic for the modern mind to grasp; it is not an institution which exists

or ceases with its observance by man; the divine rest is a fact as much as the

divine working, and so the sanctity of the day is a fact whether man secures

the benefit or not. There is little trace of the idea that the Sabbath was made

for man and not man for the Sabbath; it is an ordinance of the cosmos like any

other part of the creative operations, and is for the good of man in precisely

the same sense as the whole creation is subservient to his welfare."(2)

The Bible account of the creation of the

Sabbath "in the beginning," is not a denial of the creed of the

evolutionist. But while one may hold the theory of an evolutionary process in

the development of the universe, the Sabbath of Genesis confirms the fact that

God was not only "in the beginning," but that he stayed with his

earth as the benevolent Father of his people whom he created in his own image

and likeness.

That God created the heavens and the earth,

and at the same time instituted the Sabbath on the seventh day, was a

fundamental belief of the Hebrews. In this faith Jesus was born, and of it he

said not one jot or tittle should pass away till all is fulfilled. If the roots

of the Sabbath reach back to this ancient Scripture it is well grounded.(3) If Jesus said it can not pass away till the earth passes,

then in our Sabbath-keeping we do well to hearken to the voice of the Master.

Israel's exodus from Egypt has been referred

to as the first labor strike in history; and, again, as an early and mighty

social movement. But in the mind of the leader it was pre-eminently, if not

solely, a religious movement. Moses had met God in the wilderness, and the great

object of his mission to his people from that time forward was to lead them out

into a life of warmer faith and of fuller obedience. They were not simply

getting away from something but they were getting away to

something.

When they had put the sea between themselves

and their task-masters they came into full control of their time once more, and

were free to make their acts conform to their own desires. Then it was that the

Sabbath, the appointed witness of God's presence in the earth, again threw its

benevolent shadow across their pathway. The demand for its observance was the

call for a practical demonstration of their faith in God. The keeping of the

Sabbath was an expression of their purpose to obey all God's

commandments.

In the long years of the wilderness journey

the people were disciplined in the law of God, and were taught the necessary

rules of community life. They learned to obey God and to act for the common

good. Nothing in these important years of Israel's history had greater

influence upon their lives than the Sabbath. It occupied a central place in

their thought and experience even before it found a place in the formal

pronouncement of the law of God at Sinai.

One can not read the Ten Commandments

without realizing the fact that he is face to face with a unique and lofty

moral code.(4) These stately but practical precepts feel

as if they possessed real authority over life and conduct. The question

whether they were written by the finger of God on tables of stone need not

concern us greatly. Apart from the incidents of the giving of the law as

recorded in Scripture - the stone slabs, the smoke and fire and thunder - there

remains the greater fact of the commandments themselves. They are now on record

in the twentieth chapter of Exodus where they have been preserved for

centuries, and where they are read today by men everywhere, and learned by

heart by children of every civilized race. They formed the foundation of

religion and ethics for the Hebrews; and men of Christian faith believe it was

of these that Jesus spoke when he said: "I came not to destroy the

law."

At the heart and center of this moral code

is this commandment: "Remember the Sabbath day to keep it holy."

"The seventh day is the Sabbath of the Lord thy God." The burden of

proof would seem to rest not upon him who holds to the fourth commandment with

the rest of the decalogue, but upon him who rejects the fourth while

acknowledging the authority of the other nine. Let those who tear one out give

reason why. To Sabbath-keeping Christians it seems sufficient to hold to the

plain teachings of the Word of God.

In the later history of Israel the sins

condemned by the prophets were not ceremonial but ethical. The people were not

asked to multiply sacrifices, but to do good to others, and to walk humbly

before God. These prophets, who in life and teaching approached the Gospel

standard, taught that true Sabbath-keeping was necessary to right living. They

cried out against Sabbath-breaking, which was one of the chief sins that

brought punishment to the race. They held that spiritual Sabbath-keeping would

free the people from threatened punishment and would bring blessings in its

train.(5)

George Adam Smith comments on the

fifty-eighth chapter of Isaiah in a most illuminating way. After describing the

anti-ceremonial and highly ethical nature of the prophet's message, he

concludes his treatment of the chapter in the following manner:

"And so concludes a passage which fills

the earliest, if not the highest, place in the glorious succession of

Scriptures of Practical Love, to which belong the sixty-first chapter of

Isaiah, the twenty-fifth of Matthew and the thirteenth of First Corinthians.

Its lesson is-to go back to the figure of the draggled rose-that no mere forms

of religion, however divinely prescribed or conscientiously observed, can of

themselves lift the distraught and trailing affections of man to the light and

peace of Heaven; but that our fellow-men, if we cling to them with love and

with arms of help, are ever the strongest props by which we may rise to God;

that character grows rich and life joyful, not by the performance of ordinances

with the cold conscience of duty, but by acts of service with the warm heart of

love.

"And yet such a prophecy concludes with

an exhortation to the observance of one religious form, and places the keeping

of the Sabbath on a level with the practice of love. . . . . Observe that our

prophet bases his plea for Sabbath-keeping, and his assurance that it must lead

to prosperity, not on its physical, moral, or social benefits, but simply upon

its acknowledgment of God. Not only is the Sabbath to be honoured because it is

the 'Holy of Jehovah' and 'Honourable', but making it one's pleasure is

equivalent to 'finding one's pleasure in Him'. The parallel between these two

phrases in verse 13 and verse 14 is evident and means really this: Inasmuch as

ye do it unto the Sabbath ye do it unto Me. The prophet, then, enforces the

Sabbath simply on account of its religious and Godward aspect. . . . . Now, in

that wholesale destruction of religious forms, which took place at the

overthrow of Jerusalem, there was only one institution which was not

necessarily involved. The Sabbath did not fall with the Temple and the Altar:

the Sabbath was in. dependent of all locality; the Sabbath was possible even in

exile. It was the one solemn, public, and frequently regular form in which the

nation could turn to God, glorify Him, and enjoy Him. Perhaps, too, through the

Babylonian fashion of solemnizing the seventh day, our prophet realized again

the primitive institution of the Sabbath, and was reminded that, since seven

days is a regular part of the natural year, the Sabbath is, so to speak,

sanctioned by the statutes of Creation."(6)

Among the lessons of the Babylonian

captivity was the lesson of better Sabbath observance. As Professor Briggs well

says: "They are exhorted to be faithful to the Sabbath, the holy day of Jehovah.

All other holy things have been destroyed. All the more is their fidelity to be

shown by the sanctification of the holy day. In response to such repentance

Jehovah will come. His glory will be revealed, and his light will shine, and

dispel their darkness and gloom. He will guide them continually, and satisfy

all their needs, so that they will become like a well-watered garden; and the

wastes of Zion which have been long desolate will be rebuilt."(7)

The prophets approached the Gospel standard

of righteousness, and taught and lived a religion which brought men into a

vital relationship with God. They had no interest in matters of mere form and

ceremony. Religion as they conceived and taught it must issue in right conduct.

Again and again these prophets of old who could not tolerate a formal religion

called their people back from the apostacy of Sabbath-breaking. They exalted

the Sabbath, and assured the people that peace and prosperity would follow a

wholehearted return to the observance of God's holy day.

Jesus said he came not to destroy the

prophets; and in that declaration he sealed forever for himself and for his

followers the truths taught by these holy men of God.

A renewed spirit of loyalty was shown

immediately upon the return of the Jews from captivity. Under the inspiration

and guidance of Jehovah, Nehemiah came back to rebuild the holy city, and to

restore the temple and the temple worship. This consecrated and practical

leader was conscious of the fact that the captivity was but the natural result

of their own unfaithfulness. He was determined to hold true to all that

promised help and blessing. It is not likely that the Sabbath commandment was

considered more important than the others; but by its very nature and claims it

became the first test of obedience under the new order. Nehemiah not only

enjoined its observance, but he resisted those whose mercenary interests led

them to encroach upon its holy hours.(8) The discipline of

the exile years, with the teachings of the prophets ringing in their ears and

lodged in their hearts, brought the Hebrew race up to the birth of Christ free

from the paganism of no-Sabbathism.

CHAPTER THREE

The Sabbath in the Gospels

THE Sabbath played an important part in the

development of the Hebrew religion, which gave birth to Jesus, and which was

the bud that blossomed into Christianity. There were husks of the old religion

which fell away on account of the bursting life of the new, but one of the

petals which compose the flower of Christianity and hold its fragrance of

heavenly incense is the Holy Sabbath.

The Sabbath may be held in such a way as to

come between men and God. It may become an object of worship, rather

than a means of worship. This was the case with the Pharisees. No doubt

the spirit and practice of the Pharisees in regard to the Sabbath influenced

the church in its gradual forsaking of the Sabbath. But the Sabbath of the

Pharisees grew out of that period of Jewish history between Old Testament times

and the coming of Jesus, which produced no sacred writing and gave birth to no

prophet. Jesus, to whom was given all authority in heaven and on earth, and who

spoke not as the Pharisees, went back to the original purpose of the Sabbath,

which he said was made for man.

The Old Testament was Jesus' only Bible. In

it he was taught as a child. From it he received inspiration and instruction.

In the teachings of the Old Testament his life was grounded, and upon its

truths his faith was founded. It has been said that Jesus taught nothing new;

only new conceptions.(9) In the birth of Jesus the highest

hopes of the prophets were fulfilled.

Jesus was born in a Hebrew home, and

therefore in a Sabbath-keeping home; in a Seventh-day-Sabbath-keeping home. His

life was spent in a home that gathered up into its life all that was best in

the traditions of the race, and where the Scriptures were read and reverenced.

This was no accident. The Hebrew race in spite of its mistakes and weaknesses

had in it the elements that entered into his own life, and that furnished the

basis of his teachings. No other race could have given him birth. We find the

Master doing just what we would expect of one who had perfect discernment.

Continuing, correcting, and enlarging the conceptions of truth found in the Old

Testament, he rejected only that which the New Way found worthless. By his life

and teaching he gave larger meaning to all that had permanent worth.(10)

The Jews by ceremonial washings had washed

all the color out of their religion, burdening the Sabbath with rabbinical

restrictions. From these burdens Jesus sought to free the Sabbath; but no

recorded act of his can be construed to teach that he ever forgot its sanctity,

or disregarded its claims upon his own life. They who desired to condemn him,

and who accused him of Sabbath-breaking, could find no charge more serious than

that he healed a blind man on the Sabbath day, restored a withered hand, and

straightened the bent form of a woman long bowed down under an infirmity.(11) In passing through the grain fields Jesus did not so

much as rub out the grains to satisfy his hunger. It is true he defended his

disciples against their hypocritical accusers, but in his defense of them the

sacred character of the Sabbath was not involved.(12)

Think what kind of Sabbath-keeping Jesus

must have practiced when those who would condemn him by the strict law of the

Pharisees could find no charge more serious than these ministries of mercy on

the Sabbath day. The whole attitude of Jesus toward the Sabbath convinces us

beyond a peradventure that it was one of the institutions of the Old Testament

that had permanent worth. It must be preserved but purified. It must be

redeemed from Pharisaical formalism and restored to its primitive purpose of

blessing to all mankind. In connection with Luke's statement that the Son of

man is lord of the Sabbath,(13) one of the best Western

texts preserves a saying which may be original: "Observing a man at work

on the Sabbath, he said to him, 'Man if thou knowest what thou art doing, happy

art thou; but if thou knowest not, thou art cursed and a transgressor of the

law'."(14) The man who had in mind the principle

underlying the Sabbath regulation and responded to the call of necessity or

service to the needy was a law to himself.

Another recently discovered saying of Jesus

emphasizes the importance of Sabbath observance: "Except ye keep the

Sabbath ye shall not see the Father."(15) While these

sayings are not a part of our Gospel record, they are very ancient, and may be

authentic. They are in harmony with the speech as well as the spirit of Jesus

as set forth in our canonical gospels. Such consideration of the Sabbath

question lifts it above the plane of sectarianism, and of mere seventh-day

propagandism. Here we face the question of loyalty to Jesus Christ, and of a

spiritual conception of the Sabbath that shall make of it a constructive

religious force in a day when every spiritual resource is needed to build the

kingdom of God out of a broken humanity and a despoiled world. Truly he who announced

himself as Lord of the Sabbath when he was here on earth, is Lord of the

Sabbath today.

As the Son when on earth worked in harmony

always with the Father, so the Holy Spirit when he had descended according to

promise, took the things of Christ and made them known.(16)

The Sabbath which was made for man was established in the beginning by the

Father. It was observed by the Son, who by his spirit and attitude gave it the

stamp of a Christian institution, which increased its power to promote the

spiritual life of men. We should expect, therefore, that the first churches

established under the leadership of the Holy Spirit, the third person of the

Trinity, would be Sabbath-keeping churches. Such was the case; and for three

centuries at least, the Sabbath of the Old Testament and of Christ held its

supreme place in the Christian church.(17) Men more

anxious to maintain their traditions than to establish historical facts declare

that the Pentecostal outpouring of the Holy Spirit was on a Sunday. The day of

the week on which Jesus rose from the dead is a matter not fully

established among scholars, and certainly it is the height of presumption to

lay claim to the day of Pentecost as proof of special divine recognition of

Sunday. G. T. Purves in Hastings Dictionary of the Bible says that if

Jesus ate the passover with his disciples at the regular time, Pentecost fell

on Saturday. This same article says: "Wieseler plausibly suggests that the

festival was fixed on Sunday by the later Western Church to correspond with

Easter."(18) Every one who reads history knows that

the later church did not hesitate to adjust Christian dates to a pagan

calendar.

CHAPTER

FOUR

The Sabbath in the Early Church

THE first Christian churches were organized

by converted Jews, who of course were Sabbath-keepers, even as Jesus and his

disciples were Jews and Sabbath-keepers. Many proselytes also became

Christians, and these were numerous in this early period. The keeping of the

Sabbath was evidently one of the most noticeable changes in their outer conduct

as they went from paganism to belief in Jehovah, God of the Hebrews. It was but

another step to Christianity, and their Sabbath-keeping which had helped to

bring them thus far, was found to be a practice followed by the disciples of

the New Way.

So many pagans adopted Jewish customs that

Josephus could say: "There is not any city of the Grecians, nor any of the

barbarians, nor any nation whatsoever, whither our custom of resting on the

seventh day hath not come."(19) And a modern

authority says that the Sabbath of later Judaism became exceptionally important

"so that 'to Sabbatize' was a current phrase in the Roman Empire for

adopting the Jewish religion or customs."(20)

The Ethiopian eunuch was doubtless one of

these proselytes, who had been to Jerusalem to worship in the temple, when

Philip found him and taught him about Jesus. In the days of Jeremiah banished

Jews found a refuge in this region of the upper Nile, the modern Abyssinia, and

took their faith with them.(21) Possibly the queen's

treasurer was a descendant of one of these persecuted Jews, or more likely a

descendant of a native convert. After his baptism by Philip he carried back

home his new-found faith. If this be true, he becomes a most interesting link

in the history of the Sabbath, for Abyssinian Christians have been

Sabbath-keepers to the present time.(22)

Paul the great missionary was a Sabbath-keeper.

He was so brought up; and although he renounced the formal Jewish worship,

including new moons and Sabbaths, there is no evidence that he ever forsook the

weekly Sabbath, which was older than Judaism. From its place in the religion of

the Hebrews it was taken up into Christianity. Paul clashed with the Jews

everywhere he went, but never on the Sabbath question. We may be sure

that these strict legalists, who hounded Paul to the death, would have found

fault with his Sabbath-keeping if there had been the least occasion. Like his

Master, Paul rings true on this question.

The first European convert was a God-fearing,

Sabbath-keeping, Gentile woman. Lydia had forsaken the polytheistic faith of

paganism for belief in one God who created the heavens and the earth, as taught

by the purer religion of the Jews. Still open-minded, she accepted through

Paul's preaching the true and warmer faith of Christianity.

It was in a Sabbath-afternoon prayer meeting

that the first church in Europe was born.(23) The apostle

and his companions on that first Sabbath in a strange city were looking about

for a place of prayer. When these Sabbath-keeping followers of the Christ came

upon the Sabbath-keeping worshipers of Jehovah, everything was favorable and

the time ripe for the organization of a church of the new faith. The Philippian

church became noted for its spirit of generosity, and we are not surprised at this

when we recall the circumstances of its beginning, and the character of its

founders.

The Roman Catholic church has never claimed

Bible authority for Sunday. On the other hand, that church has repeatedly

referred to the change of the weekly day of worship from the Bible Sabbath to

Sunday as evidence of the authority of the church over the Bible.

As early as the fourth century Augustine was

sent by his mother to inquire of the Father-confessor in regard to the

"Saturday fast," which was then agitating the minds of believers. The

answer of the venerable St. Ambrose was: "Follow the church." In the

thirteenth century Thomas Aquinas, an authority in the present day Roman

Catholic confession, declared that the Lord's day depended upon the authority

of the church.

The Roman church has held consistently to

this position to the present time. The Latin Christians early began to dominate

the church, and they were not only anti-Jewish, but were anti-Eastern as well.

Between their antipathy for the East and their political ambitions in the West,

which early developed, the Roman church took on pagan elements, developing

ecclesiasticism as against the voluntary and personal faith of the first

Christians.

The primitive type of Christianity

prevailed, however, in many parts of the world, and was never wholly crushed.(24) It was early planted in the British Isles, and here the

Sabbath was kept to a late date. The evidence that St. Patrick kept the Sabbath

is not to be despised. The church in Ireland was evangelical, and accepted the

Scriptures as the rule of life, and repudiated Rome. Patrick's successor, St.

Columba, observed the Sabbath as a day of rest, but held worship on Sunday.(25) A church or society of Sabbath-keepers persisted in

Ireland to the middle of the last century, and included in its membership

members of the nobility, as well as peasants.

What has been said of Ireland is equally

true of Scotland. In commending Queen Margaret of Scotland as a Christian ruler

of the eleventh century, history says she was successful in establishing the

observance of Sunday. "For until that time the Sabbath was the day of

rest."(26) Sunday was observed as a day for worship,

but not as a day of cessation from labor.

Early in the Reformation period

Sabbath-keeping Christians were known to be living in Bohemia. While we have

only distorted accounts of these Christians, left to us by their enemies, it is

significant that Sabbath observers lived in the land of John Huss, where the

Christians were freest and most evangelical in consequence of being most

Biblical.

Other groups of Sabbath-keeping followers of

Christ have persisted to modern times. According to good authority there are

thirty million Sabbath-keeping Christians in the land of Abyssinia. An article

in a recent number of the Geographic Magazine makes reference to a group of

Sabbath-keeping Christians in Georgia of the Russian Trans-Caucasia. All these

furnish undeniable evidence that the early churches were Sabbath-keeping

churches, and that such were the churches planted by the early missionaries of

the Cross as they went everywhere preaching the Gospel. It is true that the

Sabbath, with many other elements of New Testament Christianity, was lost from

the main body of the Christian church when the latter "entered the tunnel

of the dark ages." But if these scattered Sabbath-keeping groups form no

part of the on-flowing current of Christian history, they, as bayous formed

near the source of the stream, bear testimony to the character of the waters

near the fountain head, before they were polluted by the inflowing streams of

paganism.

CHAPTER

FIVE

The No-Sabbath Theory of the Early Reformers

THE Sabbath question was revived as a part

of modern evangelical Christianity when the stream of Christian history emerged

again into the open this side the Middle Ages. It was agitated somewhat during

the Reformation in Germany, but did riot become prominent until the later years

of the English Reformation, a century after Luther's break with Rome.

Luther repudiated Rome, and acknowledged the

Bible to be the rule of faith and practice. He held the authority of the Bible

rather loosely, however, and in the matter of the Sabbath, as in the case of

the sacrament of the Lord's Supper, he held to the Roman position and accepted

the sanctions of tradition mediated through the church.

He seems to have believed that Jesus

deliberately disregarded the Sabbath, but he does not claim that either Jesus

or his disciples substituted Sunday. Such a position was not taken by any one

until much later. Luther says: "And seeing that those who preceded us

chose the Lord's-day for them, this harmless and admitted custom must not be

readily changed."(27)

Philip Melanchthon, Luther's younger

contemporary, says the church appointed the Lord's day, not as a substitute for

the Sabbath, but for the purpose of expressing the freedom of Christians from

any day. Sunday was chosen for a day of worship, not by New Testament

authority, but by the authority of the church, as an expression of its freedom

and of its authority over the Scriptures.(28)

Such reasoning is of the psychology of the adolescent

who must violate some law of life before he can convince himself of his own

freedom. He fastens himself about with enslaving bands of sin, the result of

his own deliberate choice, to prove that he can do as he pleases. It is the

elemental experience of the Garden of Eden over again, which always brings pain

and death.

The position of Calvin, the great Genevan

reformer, in regard to the Lord's day, was practically identical with that of

Luther. He says that Sunday was substituted for the Sabbath not by Christ or

his apostles, but by "the Ancients." He disputes the sanctity of

Sunday, and says it is an insult to the Jews to deny the Sabbath, and then to

claim the same sacredness for another day.(29)

Carlstadt, one of Luther's ablest

co-laborers, took an advanced position on the question of the authority of the

Bible as against that of the church. In other words, Carlstadt took the

position later assumed by evangelical Protestantism that the Bible and the

Bible alone is the rule of faith and practice for Christians. In harmony with

that position he exalted the Sabbath of the Bible.

Historical evidence is not entirely wanting

that Carlstadt not only taught the Biblical authority for the observance of the

seventh day Sabbath, but that he practiced its observance as a Christian

obligation and privilege.

To complete this phase of the discussion,

and pursue the development of the question up to the time of its appearance in

England, reference should be made to Henry Bullinger of Switzerland, and

Theodore Beza of France.

The former follows the early reformers and

accredits the change of the day to the desire of the church to get away from

Jewish ceremony. Then he advocates legal restrictions against Sunday

desecration, quoting the Jewish law regarding the Sabbath in support of his

demand for a strict Sunday law. Such men as he, and not the Sabbath-keepers of

that time, were the Judaizers. His appeal to the Bible, however, shows the

trend of the reformers who more and more felt the need of Scriptural authority

for their beliefs and practices, if they were to meet and answer the false

claims of the church of Rome.

Beza, who died in 1605 declared it to be superstition

to believe that one day is more sacred than another. Then he proceeds to

say that they keep one day in seven according to commandment; asserting

that this was the Sabbath until the time of Christ, but the Lord's day since

the resurrection.

The reformers were dead sure of the death of

formalism with the coming of Jesus, and the formalism of Rome repelled them.

They denied the claims of the Bible Sabbath because its observance smacked of

formalism. Then they turned around and accepted the day appointed by a

repudiated church because they felt that a worship day was necessary. In this

they did not follow Jesus. They interpreted him correctly as to his attitude

toward formalism. He found the Sabbath burdened with rabbinical restrictions

which defeated its spiritual ends. But he did not therefore repudiate the

Sabbath. It was instituted in the beginning by his Father, in harmony with whom

he ever worked. Jesus stripped the sacred seventh day of the Old Testament of

the hindering forms heaped upon it by the Pharisees. He restored the Holy

Sabbath of the Commandments and of the prophets to the use to which it had been

dedicated by the authority of Heaven.

No-Sabbathism was distinctly the teaching of

the early reformers. They accepted the Roman-made day, but were logical and

consistent so far as they took the position that it had no authority in

Scripture.

Being intense men and challenged by their

lives to a defense of their position against the power of the hierarchy, it is

no wonder that they centered their attack upon the more glaring abuses of the

papacy. It remained for later men to follow their' claim for Bible authority to

the logical inclusion of every matter of faith and practice. That is, so long

as the Protestant movement was purely a protest, certain particular

issues were made prominent, their prominence depending upon the strength and

persistency with which they were opposed by the Roman church. When the

Reformation movement had developed far enough to take on a positive,

constructive character of its own, then was the way open for the consideration

of every matter affecting Christian life and conduct. Then men began to seek in

the Bible a basis for every doctrine and practice of Christians. In this more

constructive period the scene of action shifted from the continent to England,

and the Sabbath occupied an important place. Christians who accepted the Bible

as the only authority in religion felt the inconsistency of observing a

Roman-made day. If they continued to keep Sunday they must attempt to find some

basis for it in the Bible. The theory of the transfer of the Sabbath from the

seventh to the first day of the week grew out of this unholy compromise, and is

therefore but four hundred years old. It was a makeshift, which gave us the

Scotland and New England Sunday, the beneficent influence of which is still

felt in American Protestantism, but which has lost its hold on the church in

the face of modern Biblical scholarship.

Prof. Adeney says: "If the tide that

threatens to sweep away the Sabbath is not stemmed there is danger of religion

itself being swept out, and of society becoming secularized and

materialized." He also says in the same article,(30)

"Dr. Hessey has shown that Sunday as 'the Lord's Day' was never identified

with the Jewish Sabbath in New Testament times, nor during the first three

centuries of Christian history. Saturday was still the Sabbath."

The "New England Sunday" was a

"Sabbath." It was based of course upon a false theory, which can not

be revived, but by which, nevertheless, it carried in the minds and hearts of those

who observed it the sanctions of Scripture.

Prof. Harnack has said that writers of

church history have not taken into sufficient account the very early entrance

of pagan influence into Christianity. Recent writers have shown a clearer

conception of this fact so important to the proper understanding of all

subsequent Christian history.

Sunday made its way into the church through

compromise. Up to the period of the Reformation it had no Sabbatic authority or

influence. Following the Reformation, for more than two centuries, and in

restricted areas dominated by evangelical Protestantism, it carried the Sabbath

atmosphere and toned up the spiritual life of those who conscientiously

observed it. From the beginning of the operation of the transfer theory, however,

there began to appear in England able and aggressive advocates of a return to

the sacred seventh day of Scripture.

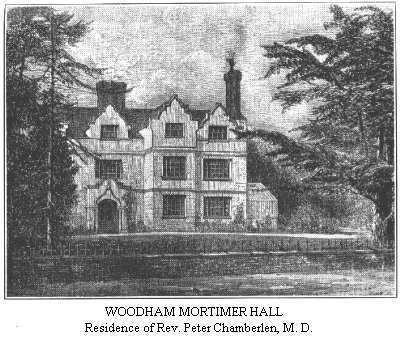

Residence of Dr. Peter

Chamberlen, M.D., 1601-1683, Pastor Mill Yard Seventh Day Baptist Church,

London, 1651-1683. Physician to three British Sovereigns.

CHAPTER

SIX

The Sabbath in the Early English Reformation

WHEN English Christianity was divorced from

Rome during the reign of Henry VIII, it became necessary to adopt a new

liturgy. As the new church, in its professions at least, was more Biblical than

the Roman church, it included in its litany the Ten Commandments. This included

of course the commandment to remember the Sabbath to keep it holy, to which

when repeated by the minister the congregation responded: "Incline our

hearts to keep this law." They were but following the Scripture of course

in including the fourth commandment; but when the minister had repeated the

commandment, and the people had asked the Lord to incline their hearts to keep

it, it became a matter of some concern among the more conscientious, and of

much debate all around, as to just what was meant.

The evangelical party maintained that in

thus employing the commandment the church acknowledged its obligation to keep

the Sabbath of Scripture. Others claimed that it should be understood as simply

enforcing the obligation to worship God, and to devote a portion of time to his

honor.

Heylyn, the High-church historian, who

accredits this to Cranmer and Ridley, thinks it was not their purpose to introduce

the Jewish Sabbath. Doubtless he is right. But it did raise the question on the

part of many as to whether they were really following the teachings of the

Bible and not the church of Rome, in their non-observance of the Sabbath of the

fourth commandment.

In its quarrel with England the Roman

Catholic church argued that since the church had displaced without question the

Sabbath day, therefore its authority was supreme, and it could make other laws.

If this premise in the question of the Sabbath were granted by the English

clergy, it would be difficult to meet other points at issue with Rome. There

was no question that the Sabbath had been set aside by the authority of Rome.

If her authority was recognized here, why not in all other matters.

Cranmer proved himself quite equal to the

occasion. His reply was both original and unique. He replied that there are two

parts to the Sabbath, and declared that "the spiritual part can not be

changed."(31)

This was the beginning of the idea of a

sacred Sabbath institution, unrelated to a particular day, and therefore

transferable.

Thus the Archbishop of Canterbury in order

to extricate himself from a compromising position made further compromise, and

laid the foundation for the "transfer" theory. This theory has

since put to sleep many a conscience which had been awakened to a sense of

Sabbath obligation by reading the plain Word of God.

Richard Greenham, a celebrated Puritan

minister who lived in the latter half of the sixteenth century, advocated

Scriptural grounds for Sunday-keeping. He declared that the Sabbath was changed

by the apostles and can not be changed again, and that Sunday must be strictly

kept. This brings us up to the publication of the celebrated work of Nicholas Bownd.(32) In this book is set forth the position since held

by all evangelical Christians who reject the Sabbath of Scripture while

claiming Bible authority for their Sunday-keeping. Not all Sunday-keeping

Christians agree in regard to the relation of Sunday to the Sabbath, but many

claim with Bownd that the one has taken over the sanctity of the other.

Another thing that brought the Sabbath into

prominence at that time was the utter disregard for Sunday as a religious rest

day. Games and sports were engaged in on that day more freely than on other

days of the week, and people abandoned all restraint in seeking their own

pleasure. Many leaders in the Church of England approved such use of the day,

and had only criticism and condemnation for those who sought to place religious

significance upon the keeping of Sunday.

On the other hand, many Christians who

recognized Bible authority for their faith became dissatisfied with anything that

fell short of the standards of Scripture. These grew increasingly bold in their

loyalty to the plain teaching of the Word.

There were two influences therefore working

to bring into prominence the Sabbath question, which held the center of the

stage in religious discussion in England for more than a hundred years. One was

the reaction against the unethical and corrupted life of the church which had

little regard for the Bible and none for the Sabbath day. The other was the

growing appreciation of the Bible as authority in religion on the part of many

honest Christians, and their refusal to accept the dictates of a corrupted

church.

The discussion growing out of this situation

was a three-cornered affair. There were those who held that there is no Sabbath

under the new dispensation, and that there should be no distinction of days in

divine service. Sunday was the day on which to assemble for worship, but after

that each might follow his regular pursuits on that day. In the second place

there were those who held to the sacredness of the seventh day of the

Scriptures and believed that the Sabbath of the Bible and of Christ is the

Sabbath of Christianity, unabrogated and binding for all time. There developed

the third class of Christians who agreed with the seventh-day advocates as to

Bible authority for the Sabbath, but who accepted the transfer theory, claiming

for the first day of the week the sanctity which the Bible gives only to the

seventh. Many went so far in trying to conform their Sunday-keeping to Scripture

as to begin its observance at sunset. A book published in London as early as

1655, written by a New England minister, contained the following argument:

"If God hath set any time to begin the Sabbath, surely 'tis such a time as

may be ordinarily and readily known, that so here (as well as in all other

ordinances) the Sabbath may be begun with prayer, and ended with praise."

Dwight L. Moody was brought up to keep

Sunday from sunset to sunset, as was many another New England boy of his

generation. So was Charles M. Sheldon's mother in western New York.

The Christian character which that custom

had a part in producing may well serve as an exhortation to those who keep the

Sabbath from sunset to sunset according to the Scriptures, to begin and close the

day in such a way as to bring them into conscious fellowship with God who

created the heavens and the earth, and who made the seventh day a time symbol

forever of his own gracious presence in the world.

CHAPTER

SEVEN

John Trask and the First Sabbatarian Church in England

AS THE atmosphere became charged with the

spirit of religious freedom, religious orders were dissolved, and the authority

of the church was denied. A new amalgamation was taking place, and the

lodestone was the Bible; a new authority in religion was being recognized-the

Holy Scriptures interpreted and obeyed in harmony with one's own knowledge and

conscience. This spirit gave birth to the Independent churches. Those who

believed in faith baptism and baptized by immersion were called Baptists. At

the very beginning of Baptist history we find those whose interpretation of

Scripture and whose loyalty to truth led them to the observance of the Sabbath

of the Bible.

The first Baptist church composed of

Englishmen was founded by Rev. John Smyth, who with his followers had gone to

Holland. Smyth at first opposed the Independents, but later accepted their

position, and even went beyond them in his adherence to the teaching of the

Word. Some members of Smyth's congregation in Holland evidently came to America

in the Mayflower group. For a century and a half in England and in the American

colonies, Baptists played an important part in the development of Biblical

Christianity and its legitimate offspring, modern democracy.

Helwys, an associate of Smyth's, returned to

England and established a church of General or Arminian Baptists in 1611. Another

congregation of Dissenters was organized in London in i6i6. Accepting the

Baptist position they sent one Blount, who "understood Dutch," to

Holland, to be baptized. On his return he baptized others, and there was

established the first Particular or Calvinistic Baptist church.

At about this same time a "Sabbatarian

Baptist" church was organized in London, the old Mill Yard church, which

has a continuous history to the present time.(33) At the

beginning as at present Baptists held to the principle of local church

autonomy. There were present from the beginning certain differences of belief

which later developed into distinct bodies, all holding the fundamental Baptist

doctrines, of faith baptism administered by immersion, religious freedom,

separation of church and state, local church independence, and the priesthood

of all believers. They soon associated themselves together for certain common

purposes of defense against the state church, and for the dissemination of

Baptist truths, especially their doctrine of the authority of the Bible.

"Sabbatarian Baptists" took their place along with the others, often

taking the position of leader and spokesman. Later in the century, during that

stirring period of English history to be treated in a subsequent volume, the

learned Dr. Joseph Stennett addressed the king on behalf of all Dissenters.

JOSEPH STENNET, D.D., 1663-1713

JOSEPH STENNET, D.D., 1663-1713

Pastor Pinner's Hall Seventh

Day Baptist Church, London, 1690-1713. Author of many hymns, including the one

beginning -

"Another six days' work

is done

Another Sabbath has

begun."

Dr. Peter Chamberlain, physician to three

sovereigns of England, was in a position to render like service. These were

both Seventh Day Baptists. No Dissenters ever suffered more on account of their

non-conformity than these Sabbath-keeping Baptists, and no roster of Christian

martyrs is complete without the name of John James, the pastor of a London

Seventh Day Baptist church.

While the early Baptist movement had

its beginning in Continental Europe, the first churches of that faith

were organized, as we have seen, in England, and were founded by ministers who

came out of the Established church. This was true of "Sabbatarian"

Baptists equally with others. One of the first names to appear in this

connection is that of John Trask.(34) He applied for

orders in the Church of England but was refused; perhaps on account of his

advanced evangelical views, for later we find him preaching as a Puritan

minister. He came to London from Somerset sometime between 1615 and 1620, where

he did the work of an evangelist. He preached not only in the city but in the

fields, thus anticipating Wesley by a hundred years in this kind of preaching.

His opposition to the Church of England is said to have been expressed in his

ranking of men into three "estates," of nature, repentance, and

grace. This sounds quite Biblical, and goes to show that he preached an

evangelical Gospel, and was no doubt in conflict with the views of the

Established church.

Trask was himself a school teacher. One of

his converts by the name of Hamlet Jackson, a tailor by trade, fired with the

evangelistic zeal of his leader, also became an evangelist. These preachers of

the Gospel in breaking away from the Established church evidently took the

Bible as their authority in religion, and true to its teachings Jackson became

a Sabbath-keeper. A vision of this truth came to him as he was walking alone in

the fields one Sunday. Possessing the courage of his convictions he began

keeping the Sabbath, and soon Trask followed his disciple in his new-found

faith.

By this time Trask had gathered about him a

company of followers, and these accepted the truth of the Sabbath with their

pastor, forming the first Seventh Day Baptist church referred to above. Jackson

later went to the Continent. Trask temporarily forsook his Sabbath-keeping

practice on account of the severe persecution which he was called upon to

suffer. In this his church did not follow him. Many of them remained true,

among them his wife, who, because of her Sabbath-keeping, spent sixteen years

in prison, where she finally died. Mrs. Trask(35) was a

school teacher also, and her services in that capacity were much in demand.

They had no free schools of course, and only tuition pupils came to her; but

she was compelled to turn many away on account of lack of room. Testimonials

are still extant which praise her as a teacher. Her disregard for the Church of

England was expressed in the request which she left in regard to the

disposition of her body after death. In that day of course, burial by "the

church" was quite necessary to insure one a place with the saved in the

heavenly kingdom! She requested that she be buried, not in the church-yard made

"holy" by the priests, but in the fields. She doubtless based her

hope for the future on obedience to, God through faith in his Son Jesus Christ,

and not upon any priestly ceremonies at death. Her desire in the matter of the

disposition of her body was carried out. Richard Lovelace, the lyric poet,

while in this same prison wrote: "To Althea from Prison." The

following lines are supposed to refer to Mrs. Trask:

"Stone

walls do not a prison make,

Nor iron bars a cage;

Minds innocent and quiet take

That for a heritage."

CHAPTER

EIGHT

Theophilus Brabourne an Able Exponent of Sabbath Truth

IN 1628 Theophilus Brabourne published his

first defense of the Sabbath. Brabourne(36) was a much

abler writer than Trask, and during thirty years he wrote four volumes in

defense of the Sabbath of the Bible. He dedicated his second volume, published

in 1632, to the king, Charles I. This was a larger book than the first one, and

was entitled: "A Defense of That Most Ancient and Sacred Ordinance of

God's, the Sabbath Day." Gilfillan says that "if on neither occasion

the author sounded the first trumpet to the fight, yet by his second publication

he blew a blast in the ear of royalty itself which compelled attention and

provoked immediate as well as lasting hostilities."

It may be well to recall the fact again that

the king and clergy of the Church of England were at this time endeavoring to restore

Sunday to the place it had held before the Reformation, as simply one of the

church's holy days. On it Christians were supposed to meet for worship, but

after the services they might pursue their own pleasures and occupations. King

James had issued a "Book of Sports," setting forth certain amusements

which the people were encouraged to engage in on Sunday, which had outraged the

Puritans.

Heylin,(37) a clergyman

in the Church of England, and one of the ablest defenders of this liberal

position, published a stupendous volume on the subject a number of years later

in which he discusses together the position of Trask and Brabourne. He calls

them consistent Puritans, and says their "conclusions in the matter of the

Seventh day Sabbath must necessarily follow the premises on which the Brownists

rejected the communion of the Church of England." It will be recalled that

it was a company of these "Brownists" who came to America in the

Mayflower, and who have been called since the Pilgrim Fathers.

In discussing the consistency of the

position of Trask and Brabourne on the Sabbath question with the Puritan

movement, Heylin declares that "Saturday was as highly honored as the

Lord's Day by the Eastern Churches, that the Lord's Day was only partly given

to religious exercises, the rest to feasting; and that Calvin cried down

dancing not because of the Lord's Day, but because of his opposition to the

sport itself." (Sunday was given over to dancing and other worldly

amusements.)

Of course the author's purpose is to condemn

Puritanism, of which he considers Sabbath-keeping a logical part.

The position of this Churchman has been given

here because it fairly represents the position of the orthodox party during

this interesting period of our history.

As might have been expected because of the

nature of the subject and the fact of its dedication to the king, Brabourne's

book stirred the ire of the powers that be. He was therefore called before the

court of the High Commission. Just what transpired there is not clear from this

distance. Hevlin says, "He altered his opinions, having been misguided in

them by some noted men in whom he thought he might have trusted."

Gilfillan says, "He confessed his error and submitted to the 'Mother

Church'." Cox says, "He quickly conformed to the Church of

England," but that "his followers did not all accompany him back

to orthodoxy."

Following his alleged recantation he is

reported to have said: "Nevertheless, if Sabbatic institution be indeed

moral and perpetually binding, the seventh day ought to be sacredly kept."

This remark reminds us of the familiar one

uttered in the same year by his learned Italian contemporary, Galileo. When

forced by the Inquisition to abjure belief in the Copernican theory of the

earth, he is said to have stamped his foot on the earth indignantly muttering,

"Yet it moves."

Whether Brabourne the Sabbatarian expressed

the impatience alleged to have been evinced in the action of Galileo the

astronomer, we may not say. He seems to have revealed the same tenacity for

truth as he believed it. He is accredited with the following judicious but

self-revealing statement: "Take your choice. But in keeping the Lord's day

and profaning the Sabbath you walk in great danger and peril (to say the least)

of transgressing one of God's eternal and inviolable laws, the Fourth

Commandment. Otherwise you are out of all gunshot of danger."

Whatever may have taken place when he was

brought before the High Commission, Theophilus Brabourne must be given an

honored place among the faithful defenders of the Sabbath truth. As late as

1659 we find him writing in defense of the Sabbath. In 1660 appeared his last

volume on the subject. The nature of the book may be judged somewhat by the

title: "Of the Sabbath day, which is now the highest controversie in

the Church of England; for of this controversie dependeth the gaining or losing

one of God's Ten Commandments, by name of the 4th Command for the Sabbath

day." Something of his character as well as his steadfastness in his

Sabbath principles is revealed in his preface to his defense of the Sabbath

published in 1659. This is twenty-seven years after his experience in the High

Commission, and he bravely writes as follows: "The soundness and clearness

of this my cause giveth me good hope that God will enlighten them (the

magistrates) with it and so incline their hearts to mercy. But if not, since I

verily believe and know it to be a truth, and my duty not to smother it, and

suffer it to die with me, I have adventured to publish it and defend it, saying

with Queen Esther, 'If I perish, I perish'; and with the apostle Paul, 'neither

is my life dear unto me, so that I may fulfill my course with joy.' What a

corrosive it would prove to my conscience, on my deathbed, to call to mind how

I knew these things full well, but would not reveal them. How could I say with

Paul, that I had revealed the whole counsel of God, and had kept nothing back

which was profitable? What hope could I then conceive that God would open his

gate of mercy to me, who, while I live, would not open my mouth for him?"

Confident of the correctness of his

position, and possessing the true Puritan conscience which held him true to his

religious convictions however unpopular they might be, he dared to face

persecution in this world, if only he could meet God with a clear conscience.

THE PLAINFIELD SEVENTH DAY BAPTIST

CHURCH OF CHRIST, PLAINFIELD, N.J.

The mother church of

Plainfield, the Piscataway Seventh Day Baptist Church, was constituted 1705.

Plainfield was organized 1838. Present building erected 1891.

CHAPTER

NINE

A Sabbath Creed of the Seventeenth Century

BRABOURNE'S last book was poorly printed

which goes to show that he had difficulty in getting it published. The king had

sought to control printing by imposing a license. By this method he thought to

suppress heretical writings. Brabourne's book was published by a foreigner

possibly, or by some private shop that lacked adequate equipment. Its contents

were of such a nature, however, that Francis White, D. D., Bishop of Ely, was

asked by the king to prepare a reply. This he did, dedicating his book to

Archbishop Laud. The author's avowed purpose was to "settle the king's

good subjects who for a long time had been disturbed by Sabbatarian

questions."

White set forth the usual arguments of the

orthodox clergymen of that time. In regard to the response to the fourth

commandment in the Book of Prayer, he says they beseech God to incline their

hearts to keep this law in such a manner as is agreeable to the state of the

Gospel and the time of grace; that is, according to the rule of Christian

liberty. He pleads church authority for the day and the manner of its

observance, and does not appeal to the Bible.

Of course not all English clergymen agreed

with these liberals. The eminent Thomas Fuller laments the looseness of

Christians regarding the observance of the Lord's Day. He says: "These

transcendents, accounting themselves mounted above the predicaments of common

piety, aver they need not keep any, because they keep all days Lord's Days in

their elevated holiness. But, alas, Christian duties, said to be ever done will

prove to be never done, if not sometimes solemnly done."

The anonymous author of "Dissenters and

Schismatics Exposed,"(38) a book which purports to

give the tenets of some fourteen "Sectaries," speaks of the

"Sabbatarians," naming Trask and Brabourne as their earliest

representatives. The doctrines held by them at the time this was written, were

stated as follows: They believe, 1. That the Fourth Commandment of the

Decalogue, Remember the Sabbath Day to keep it holy, is a Divine Precept;

simply and entirely moral, containing nothing legally ceremonial, in whole or

in part, and therefore ought to be perpetual, and to continue in full force and

virtue to the world's ends. 2. That Saturday, or the seventh day in every week,

ought to be an everlasting Holy Day in the Christian church, and the religious

observation of this day obliges Christians under the Gospel, as it did the Jews

before the coming of Christ. 3. That Sunday, or the Lord's Day, is an ordinary

working day, and it is superstition and will-worship to make the same the

Sabbath of the Fourth Commandment.

Thus by the hand of their enemies we have,

in a somewhat stilted form it is true, but nevertheless very clearly presented,

the position of Sabbath-keeping Baptists in the seventeenth century.

It will be seen that while these exponents

of Sabbath truth were called Judaizers, they observed the Sabbath as

Christians, and argued its obligation from that viewpoint. They opposed the

view held by the orthodox party as to the character and purpose of the Sabbath.

They agreed with the Puritan dissenters, that it had a sacred character, and

was to be used for religious purposes only. They went one step beyond other

dissenters, and claimed that the Sabbath of the Bible, the seventh day of the

week, was the Sabbath of Christians, and had not been changed by Christ or his

disciples.

We have discussed the conflicting views

concerning the Sabbath which obtained in England in the seventeenth century. In

this question, as many admitted, was involved the consistency of the whole

Puritan position. The authority of the Bible as opposed to the Roman Catholic

idea of the authority of the church, was involved in the discussion of the

Sabbath question.

It is a question to be reckoned with in

these days of reconstruction, economical, moral, and religious, that freedom in

the matter of interpreting the Bible, and in the manner of applying its

teachings, is the basis of modern democracy. Another fact of history which must

not be forgotten in these times is that the Puritan ideal of religion as a

personal relation of the soul to God, and of obedience to the divine will, has

produced the highest morality yet reached by any people.

For these principles the Dissenters stood.

More consistent than the others we believe were the Baptists. And most

consistent of all were those Baptists who, in harmony with the principles above

referred to, kept the Sabbath of the Bible and taught its sanctity.

It will be seen, as Heylin says, that they

built fairly on Puritan principles. These Sabbath-keeping Baptists of the first

years of the seventeenth century were Biblical and evangelical, and were the

immediate forerunners of the long list of Sabbath advocates in England and

America, known in those early years of Protestantism as Sabbatarians, and to

the present time as Seventh Day Baptists.

We close this book at the threshold of the

most interesting period of Sabbath discussion in all Christian history-the

second half of the seventeenth century. It is to be hoped that at no distant

date the story may be taken up at this point and carried through the following

century and a half of agitation, and of growing Sabbath sentiment, which led up

to the organization of the Seventh Day Baptist General Conference in 1802. This

in turn should be followed by a popular history of the denomination from the

latter date to the present.

It is a worthy history and altogether

constitutes an important chapter in the story of modern evangelical

Christianity. It is a timely topic in view of the conscious demand for-a religious

weekly rest day. The Sabbath, like every other religious question, can never be

settled till it is settled right; that is, until it is settled according to

Scripture, history, reason and religious sentiment; and upon the basis of the

highest good of man considered as a physical being, not only, but as a moral

and spiritual being.

Endnotes

1. Genesis 1:

1 - 2:3.

2. The International Critical Commentary, Genesis.

3. Bible Studies on the Sabbath Question, Main, pages 3-10. Note:

Dean Main's book contains a thorough treatment of the Bible teachings

concerning the Sabbath.

4. Exodus 20: 8-11.

5. Isaiah 58: 13, 14; Jeremiah 17: 19-27.

6. An Exposition of the Bible, Isaiah, chapter XXIII.

7. Messianic Prophecy, page 367.

8. Nehemiah 13: 15-21.

9. The Theology of the Old Testament, Davidson, pages 6-11.

10. Matthew 5:17ff.

11. John 9: 13ff; Mark 3: Iff; Luke 13: 10ff.

12. Matthew 12:1ff.

13. Luke: 6: 5.

14. The Life and Teachings of Jesus, Kent, page 92.

15. The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, article

"Logia."

16. John 14: 26,27.

17. History of Sabbath and Sunday, Lewis, chapter XII. Note:

charters XVIII and XIX carry the history of the Sabbath through the Dark Ages,

and supply much source material for this period.

18. Hastings Dictionary of the Bible, article "Pentecost."

19. The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge,

article "Sabbath."

20. The Encyclopedia of Sunday Schools and Religious Education, Vol.

III, page 940.

21. The Kings and Prophets of Israel and Judah, Kent, page 303.

22. Any reliable encyclopedia.

23. Acts 16: 11-15.

24. Seventh Day Baptists in Europe and America, Vol. 1, pages 15-17.

25. History of the Christian Church, Hurst, Vol. 1, page

625f.

26. Ibid, page 639; Celtic Scotland, Skene, Vol. 2, pages

348, 349.

27. A Critical History of the Sabbath and the Sunday, Lewis, page

229.

28. Ibid, page 234.

29. A Critical History of the Sabbath and the Sunday, Lewis, page

237-243.

30. Encyclopedia of Sunday Schools and Religious Education, article

"Sabbath."

31. A Critical History of the Sabbath and Sunday, Lewis, pages 256,

257, quotes from the Catechism.

32. History of Sabbath and Sunday, Lewis, pages 296ff.

33. Seventh Day Baptists in Europe and America, Vol. 1, pages 39-44.

34. Ibid 107 - 109.

35. Ibid 109 ­ 111.

36. Ibid 69ff.

37. A Critical History of the Sabbath and the Sunday, Lewis, Index:

"Heylin."

38. In New York City Library. Rare.