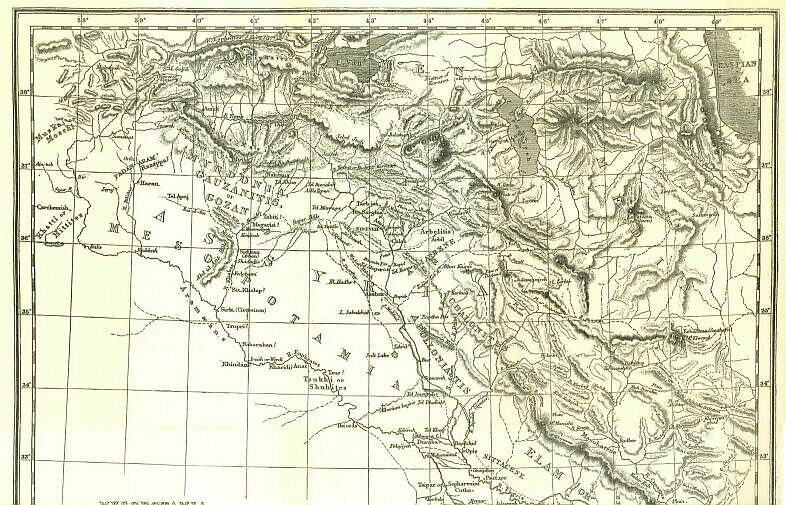

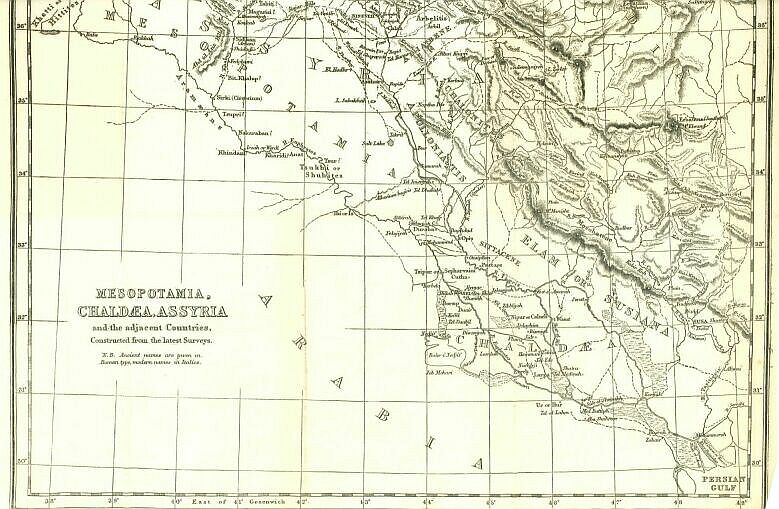

[Click on Maps to Enlarge]

|

|

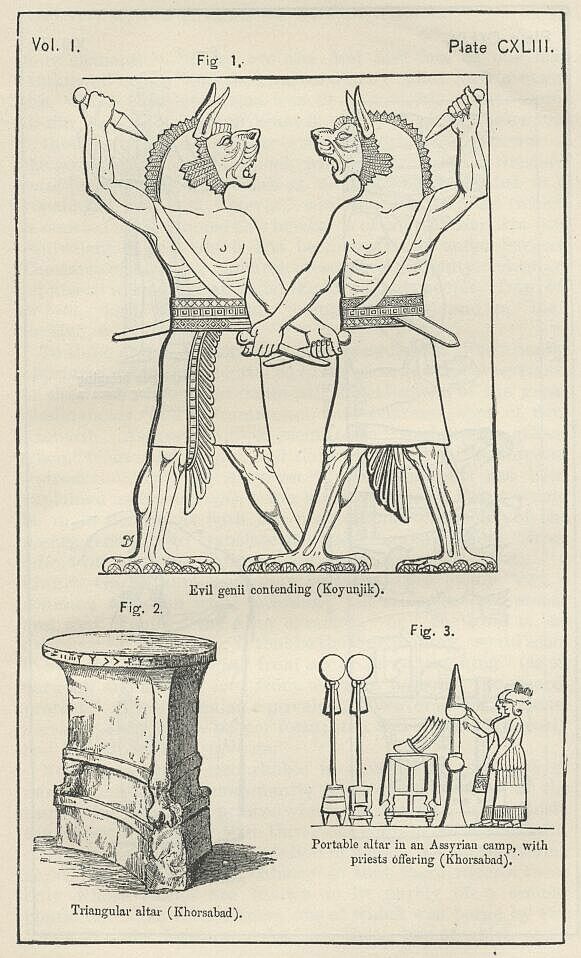

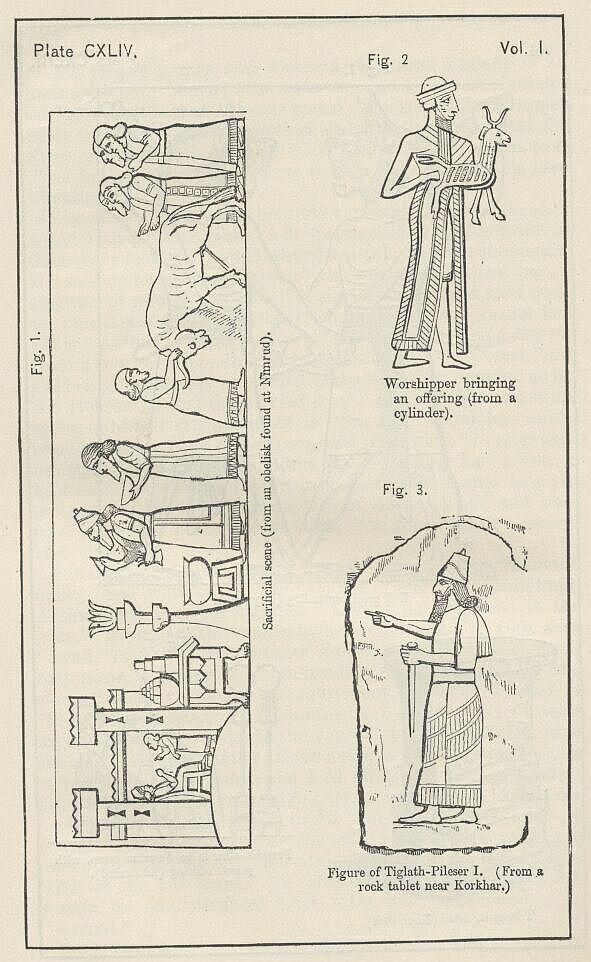

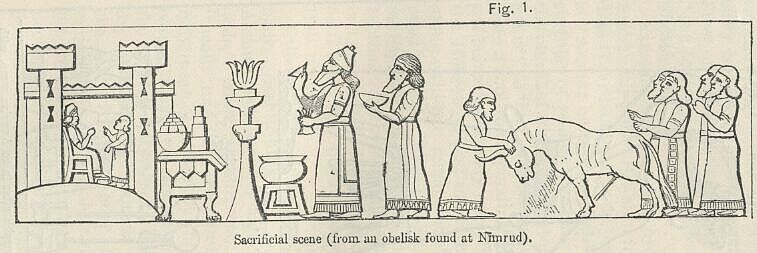

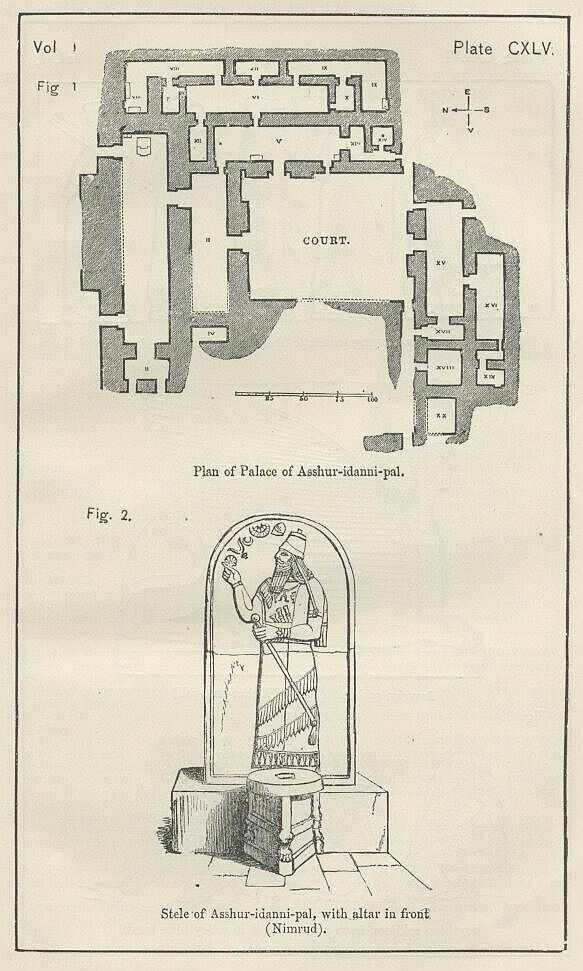

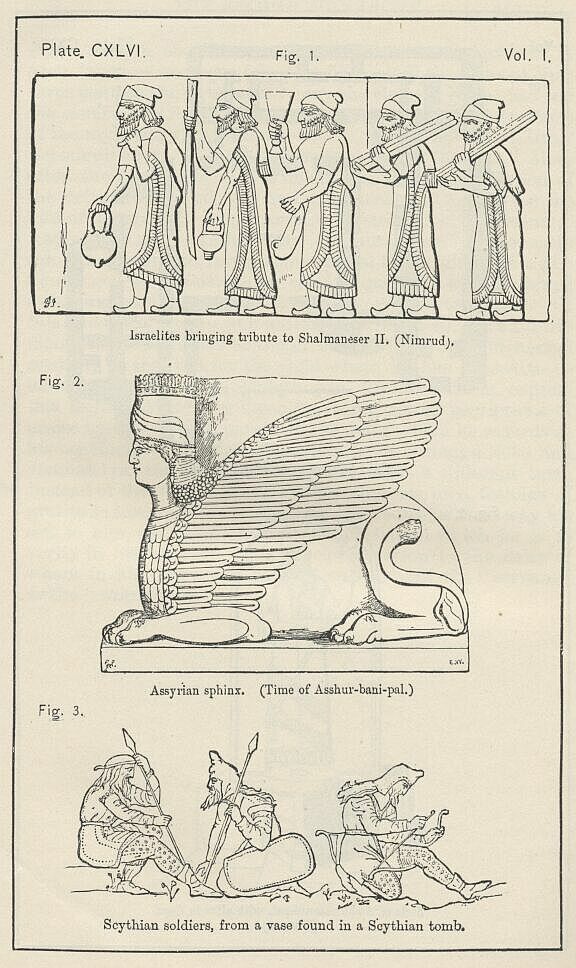

448. Evil genii contending, Koyunjik (after Boutcher) 450. Triangular altar, Khorsabad (after Botta) 451. Portable altar in an Assyrian camp, with priests offering, Khorsabad (ditto) 449. Sacrificial scene, from an obelisk found at Nimrud (ditto) 452. Worshipper bringing an offering, from a cylinder (after Lajard) 453. Figure of Tiglath-Pileser I. (from an original drawing by Mr. John Taylor) 454. Plan of the palace of Asshur-izir-pal (after Fergusson) 455. Stele of Asshur-izir-pal with an altar in front, Nimrud (from the original in the British Museum) 456. Israelites bringing tribute to Shalmaneser II., Nimrud (ditto) 457. Assyrian sphinx, time of Asshur-bani-pal (after Layard) 458. Scythian soldiers, from a vase found in a Scythian tomb |

"The graven image, and the molten image."—NAHUM i. 14

The religion of the Assyrians so nearly resembled—at least in its external aspect, in which alone we can contemplate it—the religion of the primitive Chaldaeans, that it will be unnecessary, after the full treatment which that subject received in an earlier portion of this work, to do much more than notice in the present place certain peculiarities by which it would appear that the cult of Assyria was distinguished from that of the neighboring and closely connected country. With the exception that the first god in the Babylonian Pantheon was replaced by a distinct and thoroughly national deity in the Pantheon of Assyria, and that certain deities whose position was prominent in the one occupied a subordinate position in the other, the two religious systems may be pronounced, not similar merely but identical. Each of them, without any real monotheism, commences with the same preeminence of a single deity, which is followed by the same groupings of identically the same divinities; and after that, by a multitudinous polytheism, which is chiefly of a local character. Each country, so far as we can see, has nearly the same worship-temples, altars, and ceremonies of the same type—the same religious emblems—the same ideas. The only difference here is, that in Assyria ampler evidence exists of what was material in the religious system, more abundant representations of the objects and modes of worship; so that it will be possible to give, by means of illustrations, a more graphic portraiture of the externals of the religion of the Assyrians than the scantiness of the remains permitted in the case of the primitive Chaldaeans.

At the head of the Assyrian Pantheon stood the "great god." Asshur. His usual titles are "the great Lord," "the King of all the Gods," "he who rules supreme over the Gods." Sometimes he is called "the Father of the Gods," though that is a title which is more properly assigned to Belus. His place is always first in invocations. He is regarded throughout all the Assyrian inscriptions as the especial tutelary deity both of the kings and of the country. He places the monarchs upon their throne, firmly establishes then in the government, lengthens the years of their reigns, preserves their power, protects their forts and armies, makes their name celebrated, and the like. To him they look to give them victory over their enemies, to grant them all the wishes of their heart, and to allow them to be succeeded on their thrones by their sons and their sons' sons, to a remote posterity. Their usual phrase when speaking of him is "Asshur, my lord." They represent themselves as passing their lives in his service. It is to spread his worship that they carry on their wars. They fight, ravage, destroy in his name. Finally, when they subdue a country, they are careful to "set up the emblems of Asshur," and teach the people his laws and his worship.

The tutelage of Asshur over Assyria is strongly marked by the identity of his name with that of the country, which in the original is complete. It is also indicated by the curious fact that, unlike the other gods, Asshur had no notorious temple or shrine in any particular city of Assyria, a sign that his worship was spread equally throughout the whole land, and not to any extent localized. As the national deity, he had given name to the original capital; but even at Asshur (Kileh-Sherghat) it may be doubted whether there was any building which was specially his. Therefore it is a reasonable conjectures that all the shrines throughout Assyria were open to his worship, to whatever minor god they might happen to be dedicated.

In the inscriptions the Assyrians are constantly described as "the servants of Asshur," and their enemies as "the enemies of Asshur." The Assyrian religion is "the worship of Asshur." No similar phrases are used with respect to any of the other gods of the Pantheon.

We can scarcely doubt that originally the god Asshur was the great progenitor of the race, Asshur, the son of Shen, deified. It was not long, however, before this notion was lost, and Asshur came to be viewed simply as a celestial being—the first and highest of all the divine agents who ruled over heaven and earth. It is indicative of the (comparatively speaking) elevated character of Assyrian polytheism that this exalted and awful deity continued from first to last the main object of worship, and was not superseded in the thoughts of men by the lower and more intelligible divinities, such as Shamas and Sin, the Sun and Moon, Nergal the God of War, Nin the God of Hunting, or Vul the wielder of the thunderbolt.

The favorite emblem under which the Assyrians appear to have represented Asshur in their works of art was the winged circle or globe, from which a figure in a horned cap is frequently seen to issue, sometimes simply holding a bow (Fig. I.), sometimes shooting his arrows against the Assyrians' enemies (Fig II.). This emblem has been variously explained; but the most probable conjecture would seem to be that the circle typifies eternity, while the wings express omnipresence, and the human figure symbolizes wisdom or intelligence. The emblem appears under many varieties. Sometimes the figure which issues from it has no bow, and is represented as simply extending the right hand (Fig. III.); occasionally both hands are extended, and the left holds a ring or chaplet (Fig. IV.). In one instance we see a very remarkable variation: for the complete human figure is substituted a mere pair of hands, which seem to come from behind the winged disk, the right open and exhibiting the palm, the left closed and holding a bow. In a large number of cases all sign of a person is dispensed with, the winged circle appearing alone, with the disk either plain or ornamented. On the other hand, there are one or two instances where the emblem exhibits three human heads instead of one—the central figure having on either side of it, a head, which seems to rest upon the feathers of the wing.

It is the opinion of some critics, based upon this form of the emblem, that the supreme deity of the Assyrians, whom the winged circle seems always to represent, was in reality a triune god. Now certainly the triple human form is very remarkable, and lends a color to this conjecture; but, as there is absolutely nothing, either in the statements of ancient writers, or in the Assyrian inscriptions, so far as they have been deciphered, to confirm the supposition, it can hardly be accepted as the true explanation of the phenomenon. The doctrine of the Trinity, scarcely apprehended with any distinctness even by the ancient Jews, does not appear to have been one of those which primeval revelation made known throughout the heathen world. It is a fanciful mysticism which finds a Trinity in the Eicton, Cneph, and Phtha of the Egyptians, the Oromasdes, Mithras, and Arhimanius of the Persians, and the Monas, Logos and Psyche of Pythagoras and Plato. There are abundant Triads in ancient mythology, but no real Trinity. The case of Asshur is, however, one of simple unity, He is not even regularly included in any Triad. It is possible, however, that the triple figure shows him to us in temporary combination with two other gods, who may be exceptionally represented in this way rather than by their usual emblems. Or the three heads may be merely an exaggeration of that principle of repetition which gives rise so often to a double representation of a king or a god, and which is seen at Bavian in the threefold repetition of another sacred emblem, the horned cap.

It is observable that in the sculptures the winged circle is seldom found except in immediate connection with the monarch. The great King wears it embroidered upon his robes, carries it engraved upon his cylinder, represents it above his head in the rock-tablets on which he carves his image a stands or kneels in adoration before it, fights under its shadow, under its protection returns victorious, places it conspicuously in the scenes where he himself is represented on his obelisks. And in these various representations he makes the emblem in a great measure conform to the circumstances in which he himself is engaged at the time. Where he is fighting, Asshur too has his arrow on the string, and points it against the king's adversaries. Where he is returning from victory, with the disused bow in the left hand and the right hand outstretched and elevated, Asshur takes the same attitude. In peaceful scenes the bow disappears altogether. If the king worships, the god holds out his hand to aid; if he is engaged in secular arts, the divine presence is thought to be sufficiently marked by the circle and wings without the human figure.

An emblem found in such frequent connection with the symbol of Asshur as to warrant the belief that it was attached in a special way to his worship, is the sacred or symbolical tree. Like the winged circle, this emblem has various forms. The simplest consists of a short pillar springing from a single pair of rams' horns, and surmounted by a capital composed of two pairs of rams' horns separated by one, two, or three horizontal bands; above which there is, first, a scroll resembling that which commonly surmounts the winged circle, and then a flower, very much like the "honeysuckle ornament" of the Greeks. More advanced specimens show the pillar elongated with a capital in the middle in addition to the capital at the top, while the blossom above the upper capital, and generally the stem likewise, throw out a number of similar smaller blossoms, which are sometimes replaced by fir-cones or pomegranates. Where the tree is most elaborately portrayed, we see, besides the stem and the blossoms, a complicated network of branches, which after interlacing with one another form a sort of arch surrounding the tree itself as with a frame.

It is a subject of curious speculation, whether this sacred tree does not stand connected with the Asherah of the Phoenicians, which was certainly not a "grove," in the sense in which we commonly understand that word. The Asherah which the Jews adopted from the idolatrous nations with whom they came in contact, was an artificial structure, originally of wood, but in the later times probably of metal, capable of being "set" in the temple at Jerusalem by one king, and "brought out" by another. It was a structure for which "hangings" could be made, to cover and protect it, while at the same time it was so far like a tree that it could be properly said to be "cut down," rather than "broken" or otherwise demolished. The name itself seems to imply something which stood, straight up; and the conjecture is reasonable that its essential element was "the straight stem of a tree," though whether the idea connected with the emblem was of the same nature with that which underlay the phallic rites of the Greeks is (to say the least) extremely uncertain. We have no distinct evidence that the Assyrian sacred tree was a real tangible object: it may have been, as Mr. Layard supposes, a mere type. But it is perhaps on the whole more likely to have been an actual object; in which case we can not but suspect that it stood in the Assyrian system in much the same position as the Asherah in the Phoenician, being closely connected with the worship of the supreme god, and having certainly a symbolic character, though of what exact kind it may not be easy to determine.

An analogy has been suggested between this Assyrian emblem and the Scriptural "tree of life," which is thought to be variously reflected in the multiform mythology of the East. Are not such speculations somewhat over-fanciful There is perhaps, in the emblem itself, which combines the horns of the ram—an animal noted for procreative power—with the image of a fruit or flower-producing tree, ground for supposing that some allusion is intended to the prolific or generative energy in nature; but more than this can scarcely be said without venturing upon mere speculation. The time perhaps ere long arrive when, by the interpretation of the mythological tablets of the Assyrians, their real notions on this and other kindred subjects may become known to us. Till then, it is best to remain content with such facts as are ascertainable, without seeking to penetrate mysteries at which we can but guess, and where, even if we guess aright, we cannot know that we do so.

The gods worshipped in Assyria in the next degree to Asshur appear to have been, in the early times, Anu and Vul; in the later, Bel, Sin, Shamas, Vul, Nin or Ninip, and Nergal. Gula, Ishtar, and Beltis were favorite goddesses. Hoa, Nebo, and Merodach, though occasional objects of worship, more especially under the later empire, were in far less repute in Assyria than in Babylonia; and the two last-named may almost be said to have been introduced into the former country from the latter during the historical period.

For the special characteristics of these various gods—common objects of worship to the Assyrians and the Babylonians from a very remote epoch—the reader is referred to the first part of this volume, where their several attributes and their position in the Chaldaean Pantheon have been noted. The general resemblance of the two religious systems is such, that almost everything which has been stated with respect to the gods of the First Empire may be taken us applying equally to those of the Second; and the reader is requested to make this application in all cases, except where some shade of difference, more or less strongly marked, shall be pointed out. In the following pages, without repeating what has been said in the first part of this volume, some account will be given of the worship of the principal gods in Assyria and of the chief temples dedicated to their service.

The worship of Anu seems to have been introduced into Assyria from Babylonia during the times of Chaldaean supremacy which preceded the establishment of the independent Assyrian kingdom. Shamas-Vul, the son of Ishii-Dagon, king of Chaldaea, built a temple to Anu and Vul at Asshur, which was then the Assyrian capital, about B.C. 1820. An inscription of Tiglath-Pileser I., states that this temple lasted for 621 years, when, having fallen into decay, it was taken down by Asshurdayan, his own great-grandfather. Its site remained vacant for sixty years. Then Tiglath-Pileser I., in the beginning of his reign, rebuilt the temple more magnificently than before; and from that time it seems to have remained among the principal shrines in Assyria. It was from a tradition connected with this ancient temple of Shamas-Vul, that Asshur in later times acquired the name of Telane, or "the Mound of Anu," which it bears in Stephen.

Anu's place among the "Great Gods" of Assyria is not so well marked as that of many other divinities. His name does not occur as an element in the names of kings or of other important personages. He is omitted altogether from many solemn invocations. It is doubtful whether he is one of the gods whose emblems were worn by the king and inscribed upon the rock-tablets. But, on the other hand, where he occurs in lists, he is invariably placed directly after Asshur; and he is often coupled with that deity in a way which is strongly indicative of his exalted character. Tiglath-Pileser I., though omitting him from his opening invocation, speaks of him in the latter part of his great Inscription, as his lord and protector in the next place to Asshur. Asshur-izir-pal uses expressions as if he were Anu's special votary, calling himself "him who honors Anu," or "him who honors Anu and Dugan." His son, the Black-Obelisk king, assigns him the second place in the invocation of thirteen gods with which he begins his record. The kings of the Lower Dynasty do not generally hold him in much repute; Sargon, however, is an exception, perhaps because his own name closely resembled that of a god mentioned as one of Anu's sons. Sargon not infrequently glorifies Anu, coupling him with Bel or Bil, the second god of the first Triad. He even made Anu the tutelary god of one of the gates of his new city, Bit-Sargina (Khorsabad), joining him in this capacity with the goddess Ishtar.

Anu had but few temples in Assyria. He seems to have had none at either Nineveh or Calah, and none of any importance in all Assyria, except that at Asshur. There is, however, reason, to believe that he was occasionally honored with a shrine in a temple dedicated to another deity.

BIL, or BEL.

The classical writers represent Bel as especially a Babylonian god, and scarcely mention his worship by the Assyrians; but the monuments show that the true Bel (called in the first part of this volume Bel-Nimrod) was worshipped at least as much in the northern as in the southern country. Indeed, as early as the time of Tiglath-Pileser I., the Assyrians, as a nation, were especially entitled by their monarchs "the, people of Belus;" and the same periphrasis was in use during the period of the Lower Empire. According to some authorities, a particular quarter of the city of Nineveh was denominated "the city of Belus" which would imply that it was in a peculiar way under his protection. The word Bel does not occur very frequently as an element in royal names: it was borne, however, by at least three early Assyrian kings: and there is evidence that in later times it entered as an element into the names of leading personages with almost as much frequency as Asshur.

The high rank of Bel in Assyria is very strongly marked. In the invocations his place is either the third or the second. The former is his proper position, but occasionally Anu is omitted, and the name of Bel follows immediately on that of Asshur. In one or two places he is made third, notwithstanding that Anu is omitted, Shamas, the Sun-god, being advanced over his head; but this is very unusual.

The worship of Bel in the earliest Assyrian times is marked by the royal names of Bel-snmili-kapi and Bel-lush, borne by two of the most ancient kings. He had a temple at Asshur in conjunction with Il or Ra, which must have been of great antiquity, for by the time of Tiglath-Pileser I. (B.C. 1130) it had fallen to decay and required a complete restoration, which it received from that monarch. He had another temple at Calah; besides which he had four "arks" or "tabernacles," the emplacement of which is uncertain. Among the latter kings, Sargon especially paid him honor. Besides coupling him with Anu in his royal titles, he dedicated to him—in conjunction with Beltis, his wife—one of the gates of his city, and in many passages he ascribes his royal authority to the favor of Bel and Merodach. He also calls Bel, in the dedication of the eastern gate at Khorsabad, "the establisher of the foundations of his city."

It may be suspected that the horned cap, which was no doubt a general emblem of divinity, was also in an especial way the symbol of this god. Esarhaddon states that he setup over "the image of his majesty the emblems of Asshur, the Sun, Bel, Nin, and Ishtar." The other kings always include Bel among the chief objects of their worship. We should thus expect to find his emblem among those which the kings specially affected; and as all the other common emblems are assigned to distinct gods with tolerable certainty, the horned cap alone remaining doubtful, the most reasonable conjecture seems to be that it was Bel's symbol.

It has been assumed in some quarters that the Bel of the Assyrians was identical with the Phoenician Dagon. A word which reads Da-gan is found in the native lists of divinities, and in one place the explanation attached seems to show that the term was among the titles of Bel. But this verbal resemblance between the name Dagon and one of Bel's titles is probably a mere accident, and affords no ground for assuming any connection between the two gods, who have nothing in common one with the other. The Bel of the Assyrians was certainly not their Fish-god; nor had his epithet Da-gaga any real connection with the word dag, "a fish." To speak of "Bel-Dagon" is thus to mislead the ordinary reader, who naturally supposes from the term that he is to identify the great god Belus, the second deity of the first Triad, with the fish forms upon the sculptures.

HEA, or HOA.

Hen, or Hoa, the third god of the first Triad, was not a prominent object of worship in Assyria. Asshur-izir-pal mentions him as having allotted to the four thousand deities of heaven and earth the senses of hearing, seeing, and understanding; and then, stating that the four thousand deities had transferred all these senses to himself, proceeds to take Hoa's titles, and, as it were, to identify himself with the god. His son, Shalmaneser II., the Black-Obelisk king gives Hoa his proper place in his opening invocation, mentioning him between Bel and Sin. Sargon puts one of the gates of his new city under Hoa's care, joining him with Bilat Ili—"the mistress of the gods"—who is, perhaps, the Sun-goddess, Gula. Sennacherib, after a successful expedition across a portion of the Persian Gulf, offers sacrifice to Hoa on the seashore, presenting him with a golden boat, a golden fish, and a golden coffer. But these are exceptional instances; and on the whole it is evident that in Assyria Hoa was not a favorite god. The serpent, which is his emblem, though found on the black stones recording benefactions, and frequent on the Babylonian cylinder-seals, is not adopted by the Assyrian kings among the divine symbols which they wear, or among those which they inscribe above their effigies. The word Hoa does not enter as an element into Assyrian names. The kings rarely invoke him. So far as we can tell, he had but two temples in Assyria, one at Asshur (Kileh-Sherghat) and the other at Calah (Nimrud). Perhaps the devotion of the Assyrians to Nin—the tutelary god of their kings and of their capital—who in so many respects resembled Hoa, caused the worship of Hoa to decline and that of Nin gradually to supersede it.

MYLITTA, or BELTIS.

Beltis, the "Great Mother," the feminine counterpart of Bel, ranked in Assyria next to the Triad consisting of Anu, Bel, and Hoa. She is generally mentioned in close connection with Bel, her husband, in the Assyrian records. She appears to have been regarded in Assyria as especially "the queen of fertility," or "fecundity," and so as "the queen of the lands," thus resembling the Greek Demeter, who, like Beltis, was known as: "the Great Mother." Sargon placed one of his gates under the protection of Beltis in conjunction with her husband, Bel: and Asshur-bani-pal, his great-grandson, repaired and rededicated to her a temple at Nineveh, which stood on the great mound of Koyunjik. She had another temple at Asshur, and probably a third at Calah. She seems to have been really known as Beltis in Assyria, and as Mylitta (Mulita) in Babylonia, though we should naturally have gathered the reverse from the extant classical notices.

SIN, or THE MOON.

Sin, the Moon-god, ranked next to Beltis in Assyrian mythology, and his place is thus either fifth or sixth in the full lists, according as Beltis is, or is not, inserted. His worship in the time of the early empire appears from the invocation of Tiglath-Pileser I., where he occurs in the third place, between Bel and Shamas. His emblem, the crescent, was worn by Asshur-izir-pal, and is found wherever divine symbols are inscribed over their effigies by the Assyrian kings. There is no sign which is more frequent on the cylinder-seals, whether Babylonian or Assyrian, and it would thus seem that Sin was among the most popular of Assyria's deities. His name occurs sometimes, though not so frequently as some others, in the appellations of important personages, as e, g. in that of Sennacherib, which is explained to mean "Sin multiplies brethren." Sargon, who thus named one of his sons, appears to have been specially attached to the worship of Sin, to whom, in conjunction with Shamas, he built a temple at Khorsabad, and to whom he assigned the second place among the tutelary deities of his city.

The Assyrian monarchs appear to have had a curious belief in the special antiquity of the Moon-god. When they wished to mark a very remote period, they used the expression "from the origin of the god Sin." This is perhaps a trace of the ancient connection of Assyria with Babylonia, where the earliest capital, Ur, was under the Moon-god's protection, and the most primeval temple was dedicated to his honor.

Only two temples are known to have been erected to Sin in Assyria. One is that already mentioned as dedicated by Sargon at Bit-Sargina (Khorsabad) to the Sun and Moon in conjunction. The other was at Calah, and in that Sin had no associate.

Shamas, the Sun-god, though in rank inferior to Sin, seems to have been a still more favorite and more universal object of worship. From many passages we should have gathered that he was second only to Asshur in the estimation of the Assyrian monarchs, who sometimes actually place him above Bel in their lists. His emblem, the four-rayed orb, is worn by the king upon his neck, and seen more commonly than almost any other upon the cylinder-seals. It is even in some instances united with that of Asshur, the central circle of Asshur's emblem being marked by the fourfold rays of Shamas.

The worship of Shamas was ancient in Assyria. Tiglath-Pileser I., not only names him in his invocation, but represents himself as ruling especially under his auspices. Asshur-izir-pal mentions Asshur and Shamas as the tutelary deities under whose influence he carried on his various wars. His son, the Black-Obelisk king, assigns to Shamas his proper place among the gods whose favor he invokes at the commencement of his long Inscription. The kings of the Lower Empire were even more devoted to him than their predecessors. Sargon dedicated to him the north gate of his city, in conjunction with Vul, the god of the air, built a temple to him at Khorsabad in conjunction with Sin, and assigned him the third place among the tutelary deities of his new town. Sennacherib and Esarhaddon mention his name next to Asshur's in passages where they enumerate the gods whom they regard as their chief protectors.

Excepting at Khorsabad, where he had a temple (as above mentioned) in conjunction with Sin, Shamas does not appear to have had any special buildings dedicated to his honor. His images are, however, often noticed in the lists of idols, and it is probable therefore that he received worship in temples dedicated to other deities. His emblem is generally found conjoined with that of the moon, the two being placed side by side, or the one directly under the other.

VUL, or IVA.

This god, whose name is still so uncertain, was known in Assyria from times anterior to the independence, a temple having been raised in his sole honor at Asshur, the original Assyrian capital, by Shamas-Vul, the son of the Chaldaean king Ismi-Dagon, besides the temple (already mentioned) which the same monarch dedicated to him in conjunction with Anu. These buildings having fallen to ruin by the time of Tiglath-Pileser I., were by him rebuilt from their base; and Vul, who was worshipped in both, appears to have been regarded by that monarch as one of his special "guardian deities." In the Black-Obelisk invocation Vul holds the place intermediate between Sin and Shamas, and on the same monument is recorded the fact that the king who erected it held, on one occasion, a festival to Vul in conjunction with Asshur. Sargon names Vul in the fourth place among the tutelary deities of his city, and dedicates to him the north gate in conjunction with the Sun-god, Shamas. Sennacherib speaks of hurling thunder on his enemies like Vul, and other kings use similar expressions. The term Vul was frequently employed as an element in royal and other names; and the emblem which seems to have symbolized him—the double or triple bolt—appears constantly among those worn by the kings, and engraved above their heads on the rock-tablets.

Vul had a temple at Calah besides the two temples in which he received worship at Asshur. It was dedicated to him in conjunction with the goddess Shala, who appears to have been regarded as his wife.

It is not quite certain whether we can recognize any representations of Vul in the Assyrian remains. Perhaps the figure with four wings and a horned cap, who wields a thunderbolt in either hand, and attacks therewith the monster, half lion, half eagle, which is known to us from the Nimrod sculptures, may be intended for this deity. If so, it will be reasonable also to recognize him in the figure with uplifted foot, sometimes perched upon an ox, and bearing, like the other, one or two thunderbolts, which occasionally occurs upon the cylinders. It is uncertain, however, whether the former of these figures is not one of the many different representations of Nin, the Assyrian Hercules; and, should that prove the true explanation in the one case, no very great confidence could be felt in the suggested identification in the other.

Gula, the Sum-goddess, does not occupy a very high position among the deities of Assyria. Her emblem, indeed, the eight-rayed disk, is borne, together with her husband's, by the Assyrian monarchs, and is inscribed on the rock-tablets, on the stones recording benefactions, and on the cylinder-seals, with remarkable frequency. But her name occurs rarely in the inscriptions, and, where it is found, appears low down in the lists. In the Black-Obelisk invocation, out of thirteen deities named, she is the twelfth. Elsewhere she scarcely appears, unless in inscriptions of a purely religious character. Perhaps she was commonly regarded as so much one with her husband that a separate and distinct mention of her seemed not to be requisite.

Gula is known to have had at least two temples in Assyria. One of these was at Asshur, where she was worshipped in combination with ten other deities, of whom one only, Ishtar, was of high rank. The other was at Calah, where her husband had also a temple. She is perhaps to be identified with Bilat-Ili, "the mistress of the gods," to whom Sargon dedicated one of his gates in conjunction with Hoa.

NINIP, or NIN.

Among the gods of the second order, there is none whom the Assyrians worshipped with more devotion than Nin, or Ninip. In traditions which are probably ancient, the race of their kings was derived from him, and after him was called the mighty city which ultimately became their capital. As early as the thirteenth century B.C. the name of Nin was used as an element in royal appellations; and the first king who has; left us an historical inscription regarded himself as being in an especial way under Nin's guardianship. Tiglath-Pileser I., is "the illustrious prince whom Asshur and Nin have exalted to the utmost wishes of his heart." He speaks of Nin sometimes singly, sometimes in conjunction with Asshur, as his "guardian deity." Nin and Nergal make his weapons sharp for him, and under Nin's auspices the fiercest beasts of the field fall beneath them. Asshur-izir-pal built him a magnificent temple at Nimrud (Calah). Shamas-Vul, the grandson of this king, dedicated to him the obelisk which he set up at that place in commemoration of his victories. Sargon placed his newly-built city in part under his protection, and specially invoked him to guard his magnificent palace. The ornamentation of that edifice indicated in a very striking way the reverence of the builder for this god, whose symbol, the winged bull, guarded all its main gateways, and who seems to have been actually represented by the figure strangling a lion, so conspicuous on the Hareem portal facing the great court. Nor did Sargon regard Nin as his protector only in peace. He ascribed to his influence the successful issue of his wars; and it is probably to indicate the belief which he entertained on this point that he occasionally placed Nin's emblems on the sculptures representing his expeditions. Sennacherib, the son and successor of Sargon, appears to have had much the same feelings towards Nin, as his father, since in his buildings he gave the same prominence to the winged bull and to the figure strangling the lion; placing the former at almost all his doorways, and giving the latter a conspicuous position on the grand facade of his chief palace. Esarhaddon relates that he continued in the worship of Nin, setting up his emblem over his own royal effigy, together with those of Asshur, Shamas, Bel, and Ishtar.

It appears at first sight as if, notwithstanding the general prominency of Nin in the Assyrian religious system, there was one respect in which he stood below a considerable number of the gods. We seldom find his name used openly as an element in the royal appellations. In the list of kings three only will be found with names into which the terms Nin enters. But there is reason to believe that, in the case of this god, it was usual to speak of him under a periphrasis; and this periphrasis entered into names in lieu of the god's proper designation. Five kings (if this be admitted) may be regarded as named after him, which is as large a number as we find named after any god but Vul and Asshur.

The principal temples known to have been dedicated to Nin in Assyria were at Calah, the modern Nimrud. There the vast structure at the north-western angle of the great mound, including the pyramidical eminence which is the most striking feature of the ruins, was a temple dedicated to the honor of Nin by Asshur-izir-pal, the builder of the North-West Palace. We can have little doubt that this building represents the "busta Nini" of the clasical writers, the place where Ninus (Nin or Nin-ip), who was regarded by the Greeks as the hero-founder of the nation, was interred and specially worshipped. Nin had also a second temple in this town, which bore the name of Bit-kura (or Beth-kura), as the other one did of Bit-zira (or Beth-zira). It seems to have been from the fame of Beth-zira that Nin had the title Pal-zira, which forms a substitute for Nin, as already noticed, in one of the royal names.

Most of the early kings of Assyria mention Merodach in their opening invocations, and we sometimes find an allusion in their inscriptions, which seems to imply that he was viewed as a god of great power. But he is decidedly not a favorite object of worship in Assyria until a comparatively recent period. Vul-lush III., indeed claims to have been the first to give him a prominent place in the Assyrian Pantheon; and it may be conjectured that the Babylonian expeditions of this monarch furnished the impulse which led to a modification in this respect of the Assyrian religious system. The later kings, Sargon and his successors, maintain the worship introduced by Vul-lush. Sargon habitually regards his power as conferred upon him by the combined favor of Merodach and Asshur, while Esarhaddon sculptures Merodach's emblem, together with that of Asshur, over the images of foreign gods brought to him by a suppliant prince. No temple to Merodach, is, however, known to have existed in Assyria, even under the later kings. His name, however, was not infrequently used as an element in the appellations of Assyrians.

Among the Minor gods, Nergal is one whom the Assyrians seem to have regarded with extraordinary reverence. He was the divine ancestor from whom the monarchs loved to boast that they derived their descent—the line being traceable, according to Sargon, through three hundred and fifty generations. They symbolized him by the winged lion with a human head, or possibly sometimes by the mere natural lion; and it was to mark their confident dependence on his protection that they made his emblems so conspicuous in their palaces. Nin and Nergal—the gods of war and hunting, the occupations in which the Assyrian monarchs passed their lives—were tutelary divinities of the race, the life, and the homes of the kings, who associate the two equally in their inscriptions and their sculptures.

Nergal, though thus honored by the frequent mention of his name and erection of his emblem, did not (so far as appears) often receive the tribute of a temple. Sennacherib dedicated one to him at Tarbisi (now Sherif-khan), near Khorsabad; and he may have had another at Calah (Nimrud), of which he is said to have been one of the "resident gods." But generally it would seem that the Assyrians were content to pay him honor in other ways without constructing special buildings devoted exclusively to his worship.

Ishtar was very generally worshipped by the Assyrian monarchs, who called her "their lady," and sometimes in their invocations coupled her with the supreme god Asshur. She had a very ancient temple at Asshur, the primeval capital, which Tiglath-Pileser I., repaired and beautified. Asshur-izir-pal built her a second temple at Nineveh, and she had a third at Arbela, which Asshur-bani-pal states that he restored. Sargon placed under her protection, conjointly with Anu, the western gate of his city; and his son, Sennacherib, seems to have viewed Asshur and Ishtar as the special guardians of his progeny. Asshur-bani-pal, the great hunting king was a devotee of the goddess, whom he regarded as presiding over his special diversion, the chase.

What is most remarkable in the Assyrian worship of Ishtar is the local character assigned to her. The Ishtar of Nineveh is distinguished from the Ishtar of Arbela, and both from the Ishtar of Babylon, separate addresses being made to them in one and the same invocation. It would appear that in this case there was, more decidedly than in any other, an identification of the divinity with her idols, from which resulted the multiplication of one goddess into many.

The name of Ishtar appears to have been rarely used in Assyria in royal or other appellations. It is difficult to account for this fact, which is the more remarkable, since in Phoenicia Astarte, which corresponds closely to Ishtar, is found repeatedly as an element in the royal titles.

Nebo must have been acknowledged as a god by the Assyrians from very ancient times, for his name occurs as an element in a royal appellation as early as the twelfth century B.C. He seems, however, to have been very little worshipped till the time of Vud-lush III., who first brought him prominently forward in the Pantheon of Assyria after an expedition which he conducted into Babylonia, where Nebo had always been in high favor. Vul-lush set up two statues to Nebo at Calah and probably built him the temple there which was known as Bit-Siggil, or Beth-Saggil, from whence the god derived one of his appellations. He did not receive much honor from Sargon; but both Sennacherib and Esarhaddon held him in considerable reverence, the latter even placing him above Merodach in an important invocation. Asshur-bani-pal also paid him considerable respect, mentioning him and his wife Warmita, as the deities under whose auspices he undertook certain literary labors.

It is curious that Nebo, though he may thus almost be called a late importation into Assyria, became under the Later Dynasty (apparently) one of most popular of the gods. In the latter portion of the list of Eponyms obtained from the celebrated "Canon," we find Nebo an element in the names as frequently as any other god excepting Asshur. Regarding this as a test of popularity we should say that Asshur held the first place; but that his supremacy was closely contested by Bel and Nebo, who were held in nearly equal repute, both being far in advance of any other deity.

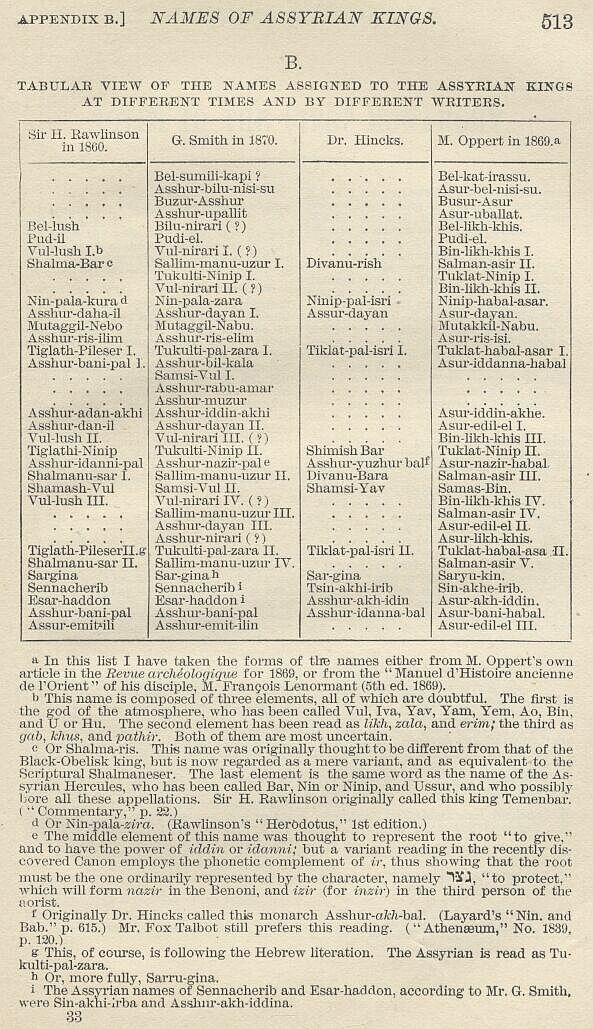

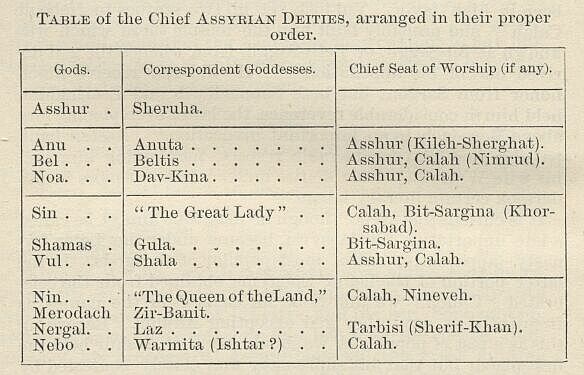

Besides these principal gods, the Assyrians acknowledged and worshipped a vast number of minor divinities, of whom, however, some few only appear to deserve special mention. It may be noticed in the first place, as a remarkable feature of this people's mythological system, that each important god was closely associated with a goddess, who is commonly called his wife, but who yet does not take rank in the Pantheon at all in accordance with the dignity of her husband. Some of these goddesses have been already mentioned, as Beltis, the feminine counterpart of Bel; Gala, the Sun-goddess, the wife of Shamas; and Ishtar, who is sometimes represented as the wife of Nebo. To the same class belong Sheruha, the wife of Asshur; Anata or Anuta, the wife of Anu; Dav-Kina, the wife of Hea or Hoa; Shales, the wife of Vul or Iva; Zir-banit, the wife of Merodach; and Laz, the wife of Nergal. Nin, the Assyrian Hercules, and Sin, the Moon-god, have also wives, whose proper names are unknown, but who are entitled respectively "the Queen of the Land" and "the great Lady." Nebo's wife, according to most of the Inscriptions, is Warmita; but occasionally, as above remarked, this name is replaced by that of Ishtar. A tabular view of the gods and goddesses, thus far, will probably be found of use by the reader towards obtaining a clear conception of the Assyrian Pantheon:

It appears to have been the general Assyrian practice to unite together in the same worship, under the same roof, the female and the male principle. The female deities had in fact, for the most part, an unsubstantial character: they were ordinarily the mere reflex image of the male, and consequently could not stand alone, but required the support of the stronger sex to give then something of substance and reality. This was the general rule; but at the same time it was not without certain exceptions. Ishtar appears almost always as an independent and unattached divinity; while Beltis and Gula are presented to us in colors as strong and a form as distinct as their husbands, Bel and Shamas. Again, there are minor goddesses, such as Telita, the goddess of the great marshes near Babylon, who stand alone, unaccompanied by any male. The minor male divinities are also, it would seem, very generally without female counterparts.

Of these minor male divinities the most noticeable are Martu, a son of Anu, who is called "the minister of the deep," and seems to correspond to the Greek Erebus; Sargana, another son of Anu, from whom Sargon is thought by some to have derived his name Idak, god of the Tigris; Supulat, lord of the Euphrates; and Il or Ra, who seems to be the Babylonian chief god transferred to Assyria, and there placed in a humble position. Besides these, cuneiform scholars recognize in the Inscriptions some scores of divine names, of more or less doubtful etymology, some of which are thought to designate distinct gods, while others may be names of deities known familiarly to us under a different appellation. Into this branch of the subject it is not proposed to enter in the present work, which addresses itself to the general reader.

It is probable that, besides gods, the Assyrians acknowledged the existence of a number of genii, some of whom they regarded as powers of good, others as powers of evil. The winged figure wearing the horned cap, which is so constantly represented as attending upon the monarch when he is employed in any sacred function, would seem to be his tutelary genius—a benignant spirit who watches over him, and protects him from the spirits of darkness. This figure commonly bears in the right hand either a pomegranate or a pine-cone, while the left is either free or else supports a sort of plaited bag or basket. Where the pine-cone is carried, it is invariably pointed towards the monarch, as if it were the means of communication between the protector and the protected, the instrument by which grace and power passed from the genius to the mortal whom he had undertaken to guard. Why the pine-cone was chosen for this purpose it is difficult to form a conjecture. Perhaps it had originally become a sacred emblem merely as a symbol of productiveness after which it was made to subserve a further purpose, without much regard to its old symbolical meaning.

The sacred basket, held in the left hand, is of still more dubious interpretation. It is an object of great elegance, always elaborately and sometimes very tastefully ornamented. Possibly it may represent the receptacle in which the divine gifts are stored, and from which they can be taken by the genius at his discretion, to be bestowed upon the mortal under his care.

Another good genius would seem to be represented by the hawk-headed figure, which is likewise found in attendance upon the monarch, attentively watching his proceedings. This figure has been called that of a god, and has been supposed to represent the Nisroch of Holy Scripture; but the only ground for such an identification is the conjectural derivation of Nisroch from a root nisr, which in some Semitic languages signifies a "hawk" or "falcon." As nisr, however, has not been found with any such meaning in Assyrian, and as the word "Nisroch" nowhere appears in the Inscriptions, it must be regarded as in the highest degree doubtful whether there is any real connection between the hawk-headed figure and the god in whose temple Sennacherib was assassinated. The various readings of the Septuagint version make it extremely uncertain what was the name actually written in the original Hebrew text. Nisroch, which is utterly unlike any divine name hitherto found in the Assyrian records, is most probable a corruption. At any rate there are no sufficient grounds for identifying the god mentioned, whatever the true reading of his name may be, with the hawk-headed figure, which has the appearance of an attendant genius rather than that of a god, and which was certainly not included among the main deities of Assyria.

Representations of evil genii are comparatively infrequent; but we can scarcely be mistaken in regarding as either an evil genius, or a representation of the evil principle, the monster—half lion, half eagle—which in the Nimrud sculptures retreats from the attacks of a god, probably Vul, who assails him with thunderbolts. [PLATE CXLIII., Fig. I.] Again, in the case of certain grotesque statuettes found at Khorsabad, one of which has already been represented, where a human figure has the head of a lion with the ears of an ass, the most natural explanation seems to be that an evil genius is intended. In another instance, where we see two monsters with heads like the statuette just mentioned, placed on human bodies, the legs of which terminate in eagles' claws—both of them armed with daggers and maces, and engaged in a struggle with one another—we seem to have a symbolical representation of the tendency of evil to turn upon itself, and reduce itself to feebleness by internal quarrel and disorder. A considerable number of instances occur in which a human figure, with the head of a hawk or eagle, threatens a winged human-headed lion—the emblem of Nergal—with a strap or mace. In these we may have a spirit of evil assailing a god, or possibly one god opposing another—the hawk-headed god or genius driving Nergal (i.e., War) beyond the Assyrian borders.

If we pass from the objects to the mode of worship in Assyria, we must notice at the outset the strongly idolatrous character of the religion. Not only were images of the gods worshipped set up, as a matter of course, in every temple dedicated to their honor, but the gods were sometimes so identified with their images as to be multiplied in popular estimation when they had several famous temples, in each of which was a famous image. Thus we hear of the Ishtar of Arbela, the Ishtar of Nineveh, and the Ishtar of Babylon, and find these goddesses invoked separately, as distinct divinities, by one and the same king in one and the same Inscription. In other cases, without this multiplication, we observe expressions which imply a similar identification of the actual god with the mere image. Tiglath-Pileser I., boasts that he has set Anu and Vul (i.e., their images) up in their places. He identifies repeatedly the images which he carries off from foreign countries with the gods of those countries. In a similar spirit Sennacherib asks, by the mouth of Rabshakeh, "Where are the gods of Hamath and of Arpad? Where are the gods of Sepharvaim, Hena, and Ivah?"—and again unable to rise to the conception of a purely spiritual deity, supposes that, because Hezekiah has destroyed all the images throughout Judaea, he has left his people without any divine protection. The carrying off of the idols from conquered countries, which we find universally practised, was not perhaps intended as a mere sign of the power of the conqueror, and of the superiority of his gods to those of his enemies; it was probably designed further to weaken those enemies by depriving them of their celestial protectors; and it may even have been viewed as strengthening of the conqueror by multiplying his divine guardians. It was certainly usual to remove the images in a reverential manner; and it was the custom to deposit them in some of the principal temples of Assyria. We may presume that there lay at the root of this practice a real belief in the super-natural power of the in images themselves, and a notion that, with the possession of the images, this power likewise changed sides and passed over from the conquered to the conquerors.

Assyrian idols were in stone, baked clay, or metal. Some images of Nebo and of Ishtar have been obtained from the ruins. Those of Nebo are standing figures, of a larger size than the human, though not greatly exceeding it. They have been much injured by time, and it is difficult to pronounce decidedly on their original workmanship: but, judging by what appears, it would seem to have been of a ruder and coarser character than that of the slabs or of the royal statues. The Nebo images are heavy, formal, inexpressive, and not over well-proportioned; but they are not wanting in a certain quiet dignity which impresses the beholder. They are unfortunately disfigured, like so many of the lions and bulls, by several lines of cuneiform writing inscribed round their bodies; but this artistic defect is pardoned by the antiquarian, who learns from the inscribed lines the fact that the statues represent Nebo, and the time and circumstances of their dedication.

Clay idols are very frequent. They are generally in a good material, and are of various sizes, yet never approaching to the full stature of humanity. Generally they are mere statuettes, less than a foot in height. Specimens have been selected for representation in the preceding volume, from which a general idea of their character is obtainable. They are, like the stone idols, formal and inexpressive in style, while they are even ruder and coarser than those figures in workmanship. We must regard them as intended chiefly for private use among the mass of the population, while we must view the stone idols as the objects of public worship in the shrines and temples.

Idols in metal have not hitherto appeared among the objects recovered from the Assyrian cities. We may conclude, however, from the passage of Nahum prefixed to this chapter, as well as from general probability, that they were known and used by the Assyrians, who seem to have even admitted them—no less than stone statues—into their temples. The ordinary metal used was no doubt bronze; but in Assyria, as in Babylonia, silver, and perhaps in some few instances gold, may have been employed for idols, in cases where they were intended as proofs to the world at large of the wealth and magnificence of a monarch.

The Assyrians worshipped their gods chiefly with sacrifices and offerings, Tiglath-Pileser I., relates that he offered sacrifice to Anu and Vul on completing the repairs of their temple. Asshur-izir-pal says that he sacrificed to the gods after embarking on the Mediterranean. Vul-lush IV, sacrificed to Bel-Merodach, Nebo, and Nergal, in their respective high seats at Babylon, Borsippa, and Cutha. Sennacherib offered sacrifices to Hoa on the sea-shore after an expedition in the Persian Gulf. Esarhaddon "slew great and costly sacrifices" at Nineveh upon completing his great palace in that capital. Sacrifice was clearly regarded as a duty by the kings generally, and was the ordinary mode by which they propitiated the favor of the national deities.

With respect to the mode of sacrifice we have only a small amount of information, derived from a very few bas-reliefs. These unite in representing the bull as the special sacrificial animal. In one we simply see a bull brought up to a temple by the king; but in another, which is more elaborate, we seem to have the whole of a sacrificial scene fairly, if not exactly, brought before us. [PLATE CXLIV., Fig. 1.] Towards the front of the temple, where the god, recognizable by his horned cap, appears seated upon a throne, with an attendant priest, who is beardless, paying adoration to him, advances a procession consisting of the king and six priests, one of whom carries a cup, while the other five are employed about the animal. The king pours a libation over a large bowl, fixed in a stand, immediately in front of a tall fire-altar, from which flames are rising. Close behind this stands the priest with a cup, from which we may suppose that the monarch will pour a second libation. Next we observe a bearded priest directly in front of the bull, checking the advance of the animal, which is not to be offered till the libation is over. The bull is also held by a pair of priests, who walk behind him and restrain him with a rope attached to one of his fore-legs a little above the hoof. Another pair of priests, following closely on the footsteps of the first pair, completes the procession: the four seem, from the position of their heads and arms, to be engaged in a solemn chant. It is probable, from the flame upon the altar, that there is to be some burning of the sacrifice; while it is evident, from the altar being of such a small size, that only certain parts of the animal can be consumed upon it. We may conclude therefore that the Assyrian sacrifices resembled those of the classical nations, consisting not of whole burnt offerings, but of a selection of choice parts, regarded as specially pleasing to the gods, which were placed upon the altar and burnt, while the remainder of the victim was consumed by priest or people.

Assyrian altars were of various shapes and sizes. One type was square, and of no great height; it had its top ornamented with gradines, below which the sides were either plain or fluted. Another which was also of moderate height, was triangular, but with a circular top, consisting of a single flat stone, perfectly plain, except that it was sometimes inscribed round the edge. [PLATE CXLIII. Fig. 2.] A third type is that represented in the sacrificial scene. [PLATE CXLIV.] This is a sort of portable stand—narrow, but of considerable height, reaching nearly to a man's chin. Altars of this kind seem to have been carried about by the Assyrians in their expeditions: we see them occasionally in the entrenched camps, and observe priests officiating at them in their dress of office. [PLATE CXLIII., Fig. 3.]

Besides their sacrifices of animals, the Assyrian kings were accustomed to deposit in the temples of their gods, as thank-offerings, many precious products from the countries which they overran in their expeditions. Stones and marbles of various kinds, rare metals, and images of foreign deities, are particularly mentioned; but it would seem to be most probable that some portion of all the more valuable articles was thus dedicated. Silver and gold were certainly used largely in the adornment of the temples, which are sometimes said to have been made "as splendid as the sun," by reason of the profuse employment upon them of these precious metals.

It is difficult to determine how the ordinary worship of the gods was conducted. The sculptures are for the most part monuments erected by kings; and when these have a religious character, they represent the performance by the kings of their own religious duties, from which little can be concluded as to the religious observances of the people. The kings seem to have united the priestly with the regal character; and in the religious scenes representing their acts of worship, no priest ever intervenes between them and the god, or appears to assume any but a very subordinate position. The king himself stands and worships in close proximity to the holy tree; with his own hand he pours libations; and it is not unlikely that he was entitled with his own arm to sacrifice victims.

But we can scarcely suppose that the people had these privileges. Sacerdotal ideas have prevailed in almost all Oriental monarchies, and it is notorious that they had a strong hold upon the neighboring and nearly connected kingdom of Babylon. The Assyrians generally, it is probable, approached the gods through their priests; and it would seem to be these priests who are represented upon the cylinders as introducing worshippers to the gods, dressed themselves in long robes, and with a curious mitre upon their heads. The worshipper seldom comes empty-handed. He carries commonly in his arms an antelope or young goat, which we may presume to be an offering intended to propitiate the deity. [PLATE CXLIV., Fig. 2.]

It is remarkable that the priests in the sculptures are generally, if not invariably, beardless. It is scarcely probable that they were eunuchs, since mutilation is in the East always regarded as a species of degradation. Perhaps they merely shaved the beard for greater cleanliness, like the priests of the Egyptians and possibly it was a custom only obligatory on the upper grades of the priesthood.

We have no evidence of the establishment of set festivals in Assyria. Apparently the monarchs decided, of their own will, when a feast should be held to any god; and, proclamation being made, the feast was held accordingly. Vast numbers, especially of the chief men, were assembled on such occasions; numerous sacrifices were offered, and the festivities lasted for several days. A considerable proportion of the worshippers were accommodated in the royal palace, to which the temple was ordinarily a mere adjunct, being fed at the king's cost, and lodged in the halls and other apartments.

The Assyrians made occasionally a religious use of fasting. The evidence on this point is confined to the Book of Jonah, which, however, distinctly shows both the fact and the nature of the usage. When a fast was proclaimed, the king, the nobles, and the people exchanged their ordinary apparel for sackcloth, sprinkled ashes upon their heads, and abstained alike from food and drink until the fast was over. The animals also that were within the walls of the city where the fast was commanded, had sackcloth placed upon them; and the same abstinence was enforced upon them as was enjoined on the inhabitants. Ordinary business was suspended, and the whole population united in prayer to Asshur, the supreme god, whose pardon they entreated, and whose favor they sought to propitiate. These proceedings were not merely formal. On the occasion mentioned in the book of Jonah, the repentance of the Ninevites seems to have been sincere. "God saw their works, that they turned from their evil way; and God repented of the evil that he had said that he would do unto them: and he did it not."

The religious sentiment appears, on the whole, to have been strong and deep-seated among the Assyrians. Although religion had not the prominence in Assyria which it possessed in Egypt, or even in Greece—although the temple was subordinated to the palace, and the most imposing of the representations of the gods were degraded to mere architectural ornaments—yet the Assyrians appear to have been really, nay, even earnestly, religious. Their religion, it must be admitted, was of a sensuous character. They not only practised image-worship, but believed in the actual power of the idols to give protection or work mischief; nor could they rise to the conception of a purely spiritual and immaterial deity. Their ordinary worship was less one of prayer than one by means of sacrifices and offerings. They could, however, we know, in the time of trouble, utter sincere prayers; and we are bound therefore to credit them with an honest purpose in respect of the many solemn addresses and invocations which occur both in their public and their private documents. The numerous mythological tablets testify to the large amount of attention which was paid to religious subjects by the learned; while the general character of their names, and the practice of inscribing sacred figures and emblems upon their signets, which was almost universal, seem to indicate a spirit of piety on the part of the mass of the people.

The sensuous cast of the religion naturally led to a pompous ceremonial, a fondness for processional display, and the use of magnificent vestments. These last are represented with great minuteness in the Nimrud sculptures. The dresses of those engaged in sacred functions seem to have been elaborately embroidered, for the most part with religious figures and emblems, such as the winged circle, the pine-cone, the pomegranate, the sacred tree, the human-headed lion, and the like. Armlets, bracelets, necklaces, and earrings were worn by the officiating priests, whose heads were either encircled with a richly-ornamented fillet, or covered with a mitre or high cap of imposing appearance. Musicians had a place in the processions, and accompanied the religious ceremonies with playing or chanting, or, in some instances, possibly with both.

It is remarkable that the religious emblems of the Assyrian are almost always free from that character of grossness which in the classical works of art, so often offends modern delicacy. The sculptured remains present us with no representations at all parallel to the phallic emblems of the Greeks. Still we are perhaps not entitled to conclude, from this comparative purity, that the Assyrian religion was really exempt from that worst feature of idolatrous systems—a licensed religious sensualism. According to Herodotus the Babylonian worship of Beltis was disgraced by a practice which even he, heathen as he was, regarded as "most shameful." Women were required once in their lives to repair to the temple of this goddess, and there offer themselves to the embrace of the first man who desired their company. In the Apocryphal Book of Baruch we find a clear allusion to the same custom, so that there can be little doubt of its having really obtained in Babylonia; but if so, it would seem to follow, almost as a matter of course, that the worship of the same identical goddess in the an joining country included a similar usage. It may be to this practice that the prophet Nahum alludes, where he denounces Nineveh as a "well-favored harlot," the multitude of whose harlotries was notorious.

Such then was the general character of the Assyrian religion. We have no means of determining whether the cosmogony of the Chaldaeans formed any part of the Assyrian system, or was confined to the lower country. No ancient writer tells us anything of the Assyrian notions on this subject, nor has the decipherment of the monuments thrown as yet any light upon it. It would be idle therefore to prolong the present chapter by speculating upon a matter concerning which we have at present no authentic data.

The chronology of the Assyrian kingdom has long exercised, and divided, the judgments of the learned. On the one hand, Ctesias and his numerous followers—including, among the ancients, Cephalion, Castor, Diodorus Siculus, Nicolas of Damascus, Trogus Pompeius, Velleius Paterculus, Josephus, Eusebius, and Moses of Chorene; among the moderns, Freret, Rollin, and Clinton have given the kingdom a duration of between thirteen and fourteen hundred years, and carried hack its antiquity to a time almost coeval with the founding of Babylon; on the other, Herodotus, Volney, Ileeren, B. G. Niebuhr, Brandis, and many others, have preferred a chronology which limits the duration of the kingdom to about six centuries and a half, and places the commencement in the thirteenth century B.C. when a flourishing empire had already existed in Chaldaea, or Babylonia, for a thousand years, or more. The questions thus mooted remain still, despite of the volumes which have been written upon them, so far undecided, that it will be necessary to entertain and discuss theirs at some length in this place, before entering on the historical sketch which is needed to complete our account of the Second Monarchy.

The duration of a single unbroken empire continuously for 1306 (or 1360) years, which is the time assigned to the Assyrian Monarchy by Ctesias, must be admitted to be a thing hard of belief, if not actually incredible. The Roman State, with all its elements of strength, had (we are told), as kingdom, commonwealth, and empire, a duration of no more than twelve centuries. The Chaldaean Monarchy lasted, as we have seen, about a thousand years, from the time of the Elamite conquest. The duration of the Parthian was about five centuries of the first Persian, less than two and a half; of the Median, at the utmost, one and a half; of the later Babylonian, less than one. The only monarchy existing under conditions at all similar to Assyria, whereto an equally long—or rather a still longer—duration has been assigned with some show of reason, is Egypt. But there it is admitted that the continuity was interrupted by the long foreign domination of the Hyksos, and by at least one other foreign conquest—that of the Ethiopian Sabacos or Shebeks. According to Ctesias, one and the same dynasty occupied the Assyrian throne during the whole period, of thirteen hundred years. Sardanapalus, the last king in his list, being the descendant and legitimate successor of Ninus.

There can be no doubt that a monarchy lasting about six centuries and a half, and ruled by at least two or three different dynasties, is per se a thing far more probable than one ruled by one and the same dynasty for more than thirteen centuries. And therefore, if the historical evidence in the two cases is at all equal—or rather, if that which supports the more improbable account does not greatly preponderate—we ought to give credence to the more moderate and probable of the two statements.

Now, putting aside authors who merely re-echo the statements of others, there seem to be, in the present case, two and two only distinct original authorities—Herodotus and Ctesias. Of these two, Herodotus is the earlier. He writes within two centuries of the termination of the Assyrian rule, whereas Ctesias writes at least thirty years later. He is of unimpeachable honesty, and may be thoroughly trusted to have reported only what he had heard. He had travelled in the East, and had done his best to obtain accurate information upon Oriental matters, consulting on the subject, among others, the Chaldaeans of Babylon. He had, moreover, taken special pains to inform himself upon all that related to Assyria, which he designed to make the subject of an elaborate work distinct from his general history.

Ctesias, like Herodotus, had had the advantage of visiting the East. It may be argued that he possessed even better opportunities than the earlier writer for becoming acquainted with the views which the Orientals entertained of their own past. Herodotus probably devoted but a few months, or at most a year or two, to his Oriental travels; Ctesias passed seventeen years at the Court of Persia. Herodotus was merely an ordinary traveller, and had no peculiar facilities for acquiring information in the East; Ctesias was court-physician to Artaxerxes Mnemon, and was thus likely to gain access to any archives which the Persian kings might have in their keeping. But these advantages seem to have been more than neutralized by the temper and spirit of the man. He commenced his work with the broad assertion that Herodotus was "a liar," and was therefore bound to differ from him when he treated of the same periods or nations. He does differ from him, and also from Thucydides, whenever they handle the same transactions; but in scarcely a single instance where he differs from either writer does his narrative seem to be worthy of credit. The cuneiform monuments, while they generally confirm Herodotus, contradict Ctesias perpetually. He is at variance with Manetho on Egyptian, with Ptolemy on Babylonian, chronology. No independent writer confirms him on any important point. His Oriental history is quite incompatible with the narrative of Scripture. On every ground, the judgment of Aristotle, of Plutarch, of Arrian, of Scaliger, and of almost all the best critics of modern times, with respect to the credibility of Ctesias, is to be maintained, and his authority is to be regarded as of the very slightest value in determining any controverted matter.

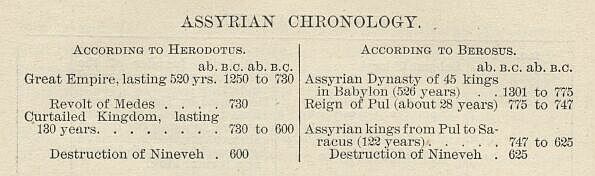

The chronology of Herodotus, which is on all accounts to be preferred, assigns the commencement of the Assyrian Empire to about B.C. 1250, or a little earlier, and gives the monarchy a duration of nearly 650 years from that time. The Assyrians, according to him, held the undisputed supremacy of Western Asia for 520 years, or from about B.C. 1250 to about B.C. 730—after which they maintained themselves in an independent but less exalted position for about 130 years longer, till nearly the close of the seventh century before our era. These dates are not indeed to be accepted without reserve; but they are approximate to the truth, and are, at any rate, greatly preferable to those of Ctesias.

The chronology of Berosus was, apparently, not very different from that of Herodotus. There can be no reasonable doubt that his sixth Babylonian dynasty represents the line of kings which ruled in Babylon during the period known as that of the Old Empire in Assyria. Now this line, which was Semitic, appears to have been placed upon the throne by the Assyrians, and to have been among the first results of that conquering energy which the Assyrians at this time began to develop. Its commencement should therefore synchronize with the foundation of an Assyrian Empire. The views of Berosus on this latter subject may be gathered from what he says of the former. Now the scheme of Berosus gave as the date of the establishment of this dynasty about the year B.C. 1300; and as Berosus undoubtedly placed the fall of the Assyrian Empire in B.C. 625, it may be concluded, and with a near approach to certainty, that he would have assigned the Empire a duration of about 675 years, making it commence with the beginning of the thirteenth century before our era, and terminate midway in the latter half of the seventh.

If this be a true account of the ideas of Berosus, his scheme of Assyrian chronology would have differed only slightly from that of Herodotus; as will be seen if we place the two schemes side by side.

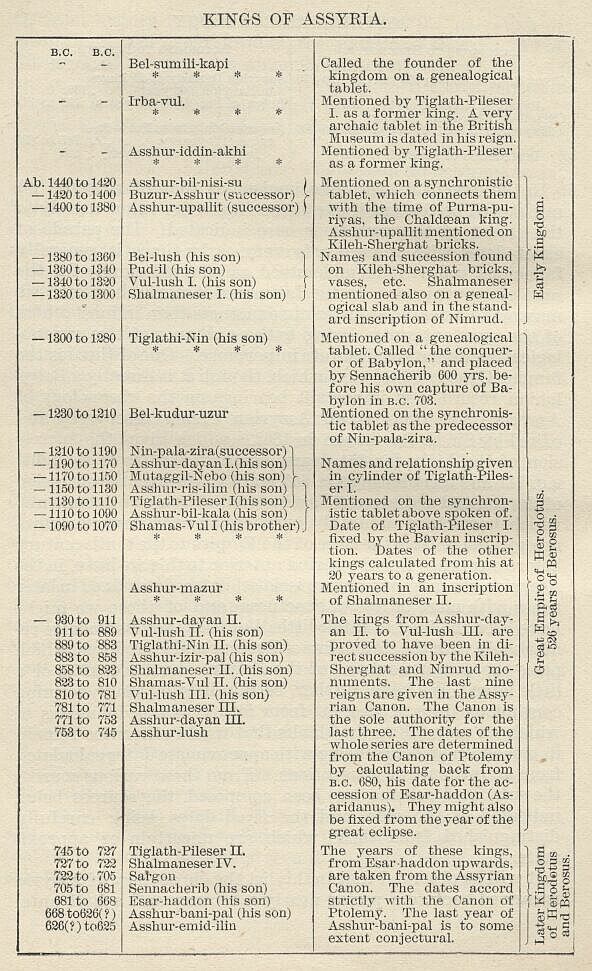

In the case of a history so ancient as that of Assyria, we might well be content if our chronology were vague merely to the extent of the variations here indicated. The parade of exact dates with reference to very early times is generally fallacious, unless it be understood as adopted simply for the sake of convenience. In the history of Assyria, however, we may make a nearer approach to exactness than in most others of the same antiquity, owing to the existence of two chronological documents of first-rate importance. One of these is the famous Canon of Ptolemy, which, though it is directly a Babylonian record, has important bearings on the chronology of Assyria. The other is an Assyrian Canon, discovered and edited by Sir H. Rawlinson in 1862, which gives the succession of the kings for 251 years, commencing (as is thought) B.C. 911 and terminating B. C. 660, eight years after the accession of the son and successor of Esarhaddon. These two documents, which harmonize admirably, carry up an exact Assyrian chronology almost from the close of the Empire to the tenth century before our era. For the period anterior to this we have, in the Assyrian records, one or two isolated dates, dates fixed in later times with more or less of exactness; and of these we might have been inclined to think little, but that they harmonize remarkably with the statements of Berosus and Herodotus, which place the commencement of the Empire about B.C. 1300, or a little later. We have, further, certain lists of kings, forming continuous lines of descent from father to son, by means of which we may fill up the blanks that would otherwise remain in our chronological scheme with approximate dates calculated from an estimate of generations. From these various sources the subjoined scheme has been composed, the sources being indicated at the side, and the fixed dates being carefully distinguished from those which are uncertain or approximate.

It will be observed that in this list the chronology of Assyria is carried back to a period nearly a century and a half anterior to B.C. 1300, the approximate date, according to Herodotus and Berosus, of the establishment of the "Empire." It might have been concluded, from the mere statement of Herodotus, that Assyria existed before the time of which he spoke, since an empire can only be formed by a people already flourishing. Assyria as an independent kingdom is the natural antecedent of Assyria as an Imperial power: and this earlier phase of her existence might reasonably have been presumed from the later. The monuments furnish distinct evidence of the time in question in the fourth, fifth, and sixth kings of the above list, who reigned while the Chaldaean empire was still flourishing in Lower Mesopotamia. Chronological and other considerations induce a belief that the four kings who follow like-wise belonged to it; and that, the "Empire" commenced with Tiglathi-Nin I., who is the first great conqueror.

The date assigned to the accession of this king, B.C. 1300, which accords so nearly with Berosus's date for the commencement of his 526 years, is obtained from the monuments in the following manner. First, Sennacherib, in an inscription set up in or about his tenth year (which was B.C. 694), states that he recovered from Babylon certain images of gods, which had been carried thither by Meroclach-idbin-akhi, king of Babylon, who had obtained them in his war with Tiglath-Pileser, king of Assyria, 418 years previously. This gives for the date of the war with Tiglath-Pileser the year B.C. 1112. As that monarch does not mention the Babylonian war in the annals which relate the events of his early years, we must suppose his defeat to have taken place towards the close of his reign, and assign him the space from B.C. 1130 to B.C. 1110, as, approximately, that during which he is likely to have held the throne. Allowing then to the six monumental kings who preceded Tiglath-Pileser average reigns of twenty years each, which is the actual average furnished by the lines of direct descent in Assyria, where the length of each reign is known, and allowing fifty years for the break between Tiglathi-Nin and Bel-kudur-uzur, we are brought to (1130 + 120 + 50) B.C. 1300 for the accession of the first Tiglathi-Nin, who took Babylon, and is the first king of whom extensive conquests are recorded. Secondly. Sennacherib in another inscription reckons 600 years from his first conquest of Babylon (B.C. 703) to a year in the reign of this monarch. This "six hundred" may be used as a round number; but as Sennacherib considered that he had the means of calculating exactly, he would probably not have used a round number, unless it was tolerably near to the truth. Six hundred years before B.C. 703 brings us to B.C. 1303.

The chief uncertainty which attaches to the numbers in this part of the list arises from the fact that the nine kings from Tiglathi-Nin downwards do not form a single direct line. The inscriptions fail to connect Bel-kudur-uzur with Tiglathi-Nin, and there is thus a probable interval between the two reigns, the length of which can only be conjectured.

The dates assigned to the later kings, from Vul-lush II., to Esarhaddon inclusive, are derived from the Assyrian Canon taken in combination with the famous Canon of Ptolemy. The agreement between these documents, and between the latter and the Assyrian records generally, is exact; and a conformation is thus afforded to Ptolemy which is of no small importance. The dates from the accession of Vul-lush II. (B.C. 911) to the death of Esarhaddon (B.C. 668) would seem to have the same degree of accuracy and certainty which has been generally admitted to attach to the numbers of Ptolemy. They have been confirmed by the notice of a great eclipse in the eighth year of Asshur-dayan III., which is undoubtedly that of June 15, B.C. 763.

The reign of Asshur-bani-pal (Sardanapalus), the son and successor of Esarhaddon, which commenced B.C. 668, is carried down to B.C. 626 on the combined authority of Berosus, Ptolemy, and the monuments. The monuments show that Asshur-bani-pal proclaimed himself king of Babylon after the death of Saul-mugina whose last year was (according to Ptolemy) B.C. 647: and that from the date of this proclamation he reigned over Babylon at least twenty years. Polyhistor, who reports Berosus, has left us statements which are in close accordance, and from which we gather that the exact length of the reign of Asshur-bani-pal over Babylon was twenty-one years. Hence, B.C. 626 is obtained as the year of his death. As Nineveh appears to have been destroyed B.C. 625 or 624, two years only are left for Asshur-bani-pal's son and successor, Asshur-emid-illin, the Saracus of Abydenus.

The framework of Assyrian chronology being thus approximately, and, to some extent, provisionally settled, we may proceed to arrange upon it the facts so far as they have come down to us, of Assyrian history.